And so the art education system today is not just the most extensive form of patronage for the living arts in this country: it is the soil without which the arts would just not be able to survive at all. I would go so far as to say that the primary task of the art schools in general, and of Fine Art courses in particular, should be to hold open this residual space for ‘the aesthetic dimension’. In one sense, this is a conservative function—like preserving the forests, or protecting whales. But in another it is profoundly radical: it involves the affirmation that a significant dimension of human experience is endangered in the present, but could come to life again in the future, and once more become a vital element in social life. In other words—and this really is at the root of all the problems in art education—it is the destiny of the art schools, if they are successful, to stand as an indictment of that form of society in which they exist and upon whose governments they are dependent for all their resources.

In such a situation, of course, it is inevitable that art education should be fraught with contradictions and conflicts about its aims and functions. Although the battle lines are rarely clearly drawn, the underlying struggles are usually pretty much the same: they are between those who are basically ‘collaborationist’ in outlook towards the existing culture, and those who perceive that the pursuit of ‘the aesthetic dimension’ involves a rupture with, and refusal of, the means of production and reproduction peculiar to that culture. This may sound a bit complicated, so let me give you a specific example: some of you may have read in the press some months ago about the battles at the Royal College of Art in London. Basically, these were about the ‘usefulness’ of painting and sculpture as taught in the Fine Art Faculty.

Richard Guyatt, who was then the rector, wanted the College to become a servant of industry. Guyatt had a background in advertising and the Graphic Arts: indeed, he was personally responsible for such triumphs of modern design as the Silver Jubilee stamps, the Anchor Butter wrapper, and a commemorative coin for the Queen Mother, issued in 1980. Predictably, when Guyatt was subjected to pressures from the Department of Education and Science, he responded by trying to drive the College along in a commercial, design orientated direction. As The Guardian commented, one question under debate was ‘whether scarce resources formerly offered to scruffy painters and sculptors should be switched to designers who might make some concrete contribution to Britain’s export drive.’

Inevitably, Guyatt clashed heavily with Peter De Francia, Professor of Painting, who clearly thought that it was preferable to teach students to create a ‘new reality’ within the illusory space of a picture, rather than to encourage them to design coins so ugly that consumers would want to get rid of them quickly in return for the slippery delights of New Zealand dairy products, or whatever. The battle was long and hard fought. Fortunately, given the support of his students, De Francia was able to win in the end: he remains as Professor of Painting, whereas Guyatt is no longer rector. But I have not brought this up as an example of academic intrigue: the Royal College affair was symptomatic of that struggle which has constantly to be waged against the anaesthetizing encroachments of the cultural collaborationists, even within the art schools themselves.

Of course, it is not often that the values of a major painter are so starkly pitted against those of a designer of coinage and butter-wrappers. In this situation, I think that most people who are involved, in any way, with the Fine Arts would have little doubt about where we stood. But, of course, it is not always as simple as that, and a major problem in recent years has been the betrayal of the ‘aesthetic dimension’ within Fine Art courses themselves. Indeed, I do not think that it is just a matter of protecting and conserving Fine Art courses against the Guyatt’s of this world, but rather one of reforming and rebuilding them, above all of undoing some of the damage that has been done, especially since the last war.

You could, I think, see something of this damage in a recent exhibition ‘A Continuing Process: The New Creativity in British Art Education, 1955-65’, which told the story of the establishment of the so-called ‘basic design’ courses, for Fine Art students, and of the way in which they proliferated until they became, effectively, the orthodoxy for a higher education in art. ‘Basic design’ was pioneered at the University in Newcastle by Victor Pasmore and Richard Hamilton, and elsewhere, along rather different lines, by Harry Thubron and Tom Hudson.

The fundamental premises of ‘basic design’ are not easily identifiable; the various artist-teachers involved in the movement pursued different, and sometimes contradictory, emphases. But this much can be said with certainty: they are all united negatively. ‘Basic design’ involved a wholesale rejection of the academic methods of art education, rooted in the study of the figure and traditional ornamentation. As Dick Field has written, the watchword of the ‘basic design’ pioneers was ‘a New Art for a New Age’, and they set out to be deliberately iconoclastic towards what had become established academic methods of teaching art.

David Thistlewood, who organized the exhibition, has written that, as a result of ‘basic design’, ‘The aims and objectives underlying a post-school art education in this country have changed utterly during the past twenty-five years.’ He says that ‘Principles which seem today to be liberal, humanist and self-evidently right would have been considered anarchic, subversive and destructive as recently as the 1940s.’ He claims that what used to exist, the old academic system, was ‘devoted to conformity, to a misconceived sense of belonging to a classical tradition, to a belief that art was essentially technical skill.’ For decades before the arrival of ‘basic design’, Thistlewood complains, there had been unhealthy preoccupations with drawing and painting according to set procedures; with the use of traditional subject- matter—the Life Model, Still-Life, and the Antique—witn the ‘application’ of art in the execution of designs; and above all with the monitoring of progress by frequent examinations. But, he claims, the advent of the new methods of teaching art constituted a ‘revolution’ against all that: in its place there now exists ‘a general devotion to the principle of individual creative development.’

But was the advent of ‘basic design’ such an unmitigatedly beneficial occurrence? Far be it from me to defend the old academicism; nonetheless, I believe that British art education of the last quarter of a century has, in general, been peculiarly disastrous and the sort of thinking that went into ‘basic design’ has had a lot to do with this. It is not just that today, instead of providing an alternative to academicism, ‘basic design’ is itself a new academicism (i.e. it is just about as ‘revolutionary’ as Leonid Brezhnev!) I also believe that, from the beginning, it exerted a restrictive and finally ‘collaborationist’ influence. I think we really need to get rid of most—although not quite all—of the attitudes which it embodies if art education is to become truly healthy.

Evidently, I cannot do justice to ‘basic design’ philosophy here, but I want to draw attention to two of its most fundamental assumptions—which I believe to be wrongheaded. The first of these is the attitude to ‘Child Art’, which one finds in Pasmore and Hudson in particular, and which has had an extraordinary effect upon the way in which most art students have been taught in recent decades. To put it crudely, the ‘basic design’ view seems to be that the intuitive and imaginative faculties of the child are repressed by culture, and the primary function of art education of adolescents should be to restore that earlier pristine state. Thus the spontaneous and intuitive productions of the child are often supposed to be paradigms of human creativity. All art is assumed to aspire to the condition of infantilism.

I have to be careful here because I believe that enormous gains were made through the recognition of a ‘natural’ potentiality for creativity in all children. As a result of the ‘Child Art’ movement, which began in the nineteenth century and gathered pace throughout the first half of the twentieth, art slowly came to play an integral part in nursery, primary and secondary school education. The ‘Child Art’ movement underlined the fact that learning was not just a matter of the acquisition of knowledge and functional skills: creative living also involved the development of imaginative, intuitive and affective faculties of the kind which play such a conspicuous part in the making of art. And so this movement stressed the fact that the capacity for creative work is an innate, biologically given, potentiality of every human being, of whatever age, class, culture, or condition. This affirmation seems to me to have an importance extending far beyond its immediate applications in nursery, primary, and secondary school education. Nonetheless, there is a great gulf between the acknowledgement of the child’s capacity for creativity, and describing that creativity as some kind of exemplar, or epitome, for adult art.

Indeed, I have been forced to the conclusion that, healthy as the ‘Child Art’ movement may have been, in itself, it was also symptomatic of a profound cultural loss: that is the loss of what I have called the ‘aesthetic dimension’ in adult, social life, of the space for imaginative and fully creative work among those who are no longer children. Surely, in an aesthetically healthy society, the capacity for creative work should develop continuously from the spontaneously individualistic self- expressions of the child (shaped by the proccesses of psycho- biological growth and development) into more complex, meaningful, and fully social (but no less creative) productions of the adult. I came to realize that we have tended to fetishize ‘Child Art’ to such a degree only because aesthetic creativity is so rare in our society at other developmental stages.

To put it another way: I suggested earlier that Bali was an ‘aesthetically healthy’ society. In what sense could a Balinese painter recognize an infant’s immature aesthetic activities as any kind of model for his own? Think, too, of those forms of aesthetic creativity manifest in, say, Amerindian rugs, the Parthenon frieze, Islamic tiles, or those magnificent carvings of leaves which cluster round the tops of the Gothic pillars in the Chapter House of Southwell Minster. Such forms of art do not seem to me, in any way, to contradict the growth of ‘individual creative development’; but, in such instances, that development has been allowed to mature, to rise beyond and above the infantile, through an adult, social, aesthetic practice.

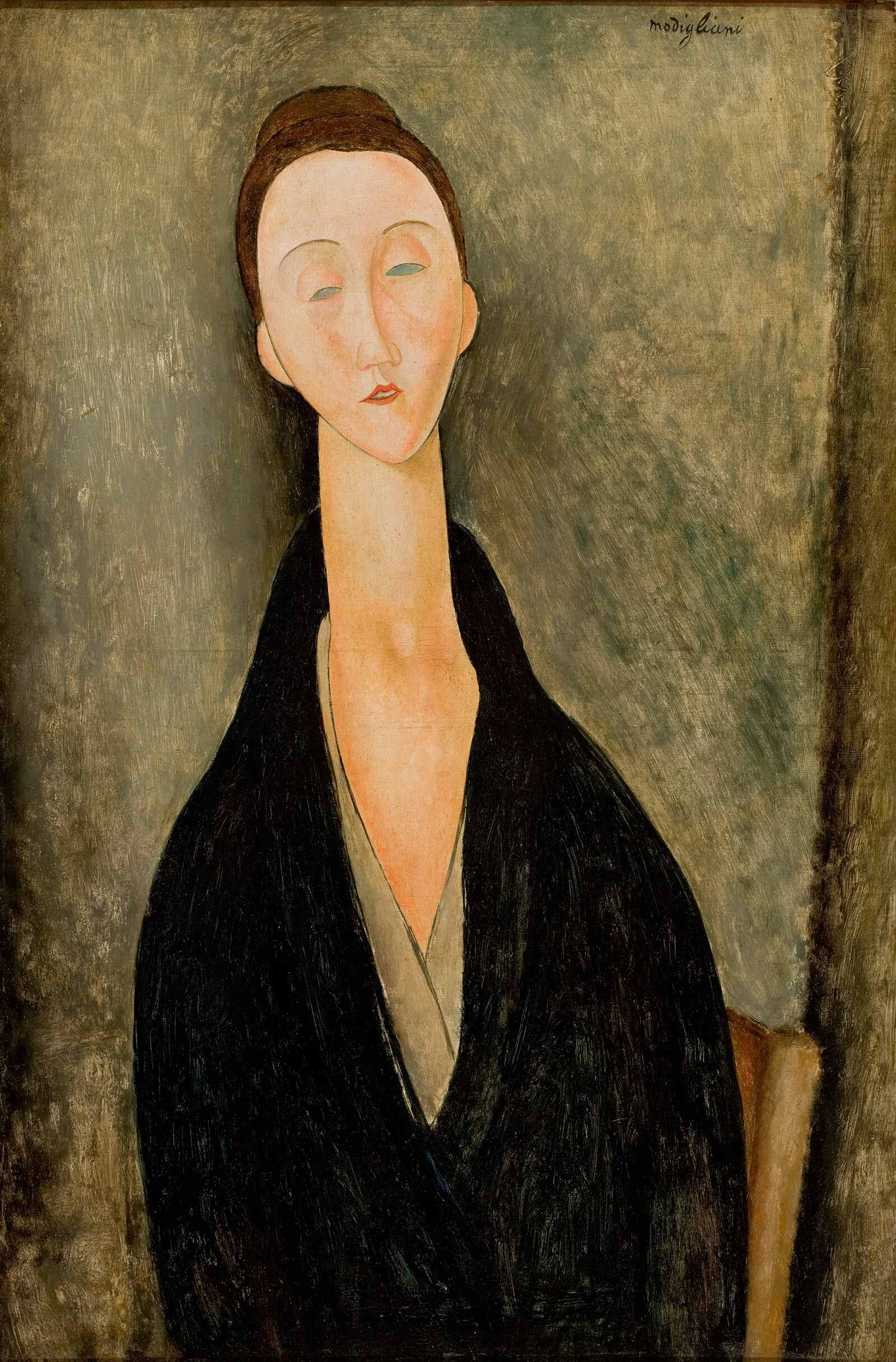

Even when such practices were driven out of the everyday fabric of life and work, painting and sculpture permitted the creation of a new and definite reality within the existing one, an illusory, re-constituted world within which the aesthetic dimension could survive, mature, and truly develop. Again, as soon as we ask in what sense ‘Child Art’ could have provided an exemplar for, say, Michelangelo, Poussin, Vermeer, or Bonnard, we begin to realize that the celebration of ‘Child Art’ may have reflected an extension of human experience in one direction, but it also revealed its diminution in another.

So one of my quarrels with recent art education in general and with ‘basic design’ in particular is that by venerating ‘Child Art’ as the paradigm of human creativity and expressive activity, they have not, as they claim, served the cause of ‘individual creative development.’ Rather, they have simply institutionalized the fact that we live in the sort of society in which such development tends to be arrested at the infantile level: i.e. everyone engages in the arts in our society, but only up until the age of about thirteen. In my view, higher education in the Fine Arts should involve the search for ways of breaking out of this aesthetic retardation rather than the celebration of it. The child may paint solely through bold, impulsive gestures, covering his surface in a matter of seconds: but that, to my mind, is no good reason why art students up and down the country should seek to imitate him.