The latest Edward Burne-Jones exhibition at the TATE reminded me of my father’s review of The Last Romantics exhibition in the 90s, at the start of the Pre-Raphaelite revival of which he was a leading voice. As part of The Peter Fuller Project I am posting the below article.

The debate with Waldemar Januszczak is particularly funny and enlightening.

THE LAST ROMANTICS

Essay by Peter Fuller - Art by Burne-Jones & Stanley Spencer

The exhibition, The Last Romantics: The Romantic Tradition in British Art, Burne-Jones to Stanley Spencer, at the Barbican Gallery in April 1989, added fuel to debates which have been simmering about the clash between Romanticism and Modernism, between 'national tradition' and 'internationalism', and between 'populism' and the 'avant-garde'. The argument which informed the exhibition was that Pre-Raphaelitism was not, as had so often previously been assumed, a cul-de-sac. On the contrary, John Christian, who brought together more than 300 works for the show, wished to demonstrate that even after the death of Burne-Jones in 1898, a Romantic tradition, deriving from Pre-Raphaelitism, persisted here, and gave rise to a great diversity of twentieth-century painting and sculpture.

Christian argued that this exhibition fills in the gap between the point where The Pre-Raphaelites, at the Tate Gallery in 1985, left off and the rise of Romanticism at the time of the second world war, as chronicled in the 1987 Barbican show, A Paradise Lost: the Neo-Romantic Imagination in Britain, 1935-1955. This amounts to more than a matter of academic art history. Christian sought to demonstrate that a Romantic tradition has been continuous in Britain, and that it persisted through the period when the Modern movement was supposed to have overthrown, or at least displaced it. What makes all this peculiarly urgent is the resurgence of a Romantic sensibility in painting in the 1980s, and the re-emergence of interest in Romantic, as opposed to Modernist, critical approaches.

The hostility of the protagonists of the Modern movement to Romanticism in general and to Pre-Raphaelitism in particular, is legendary. Christian quotes George Moore, the champion of Impressionism and the New English Art Club, who described Burne-Jones as 'the worst artist that ever lived, whether you regard him as a colourist, a draughtsman, a painter or a designer'. This view was reiterated by Bloomsbury, for whom opposition to Pre-Raphaelitism was de rigueur. Clive Bell, notoriously, swept all Pre-Raphaelitism aside, declaring it was of 'utter insignificance in the history of European culture'.

In the 1920s, a derisory view of Romanticism in general, and of Pre-Raphaelitism in particular, became part of received opinion in 'progressive' artistic circles. (Late Turner remained virtually unknown; Constable was praised as the forerunner of Impressionism!) Clive Bell's son, Quentin Bell, has described how between 1900 and 1940, no one thought the Pre- Raphaelites were worth attending to, and so no serious historical studies of them were published.

All this changed with the rise of Neo-Romanticism in the late 1930s and 1940s, and the recovery of the Romantic sensibility by painters like John Piper and critics like Robin Ironside, who wrote, so vividly, about 'a reaction from the ideas of Roger Fry, a return to freedom of attitude more easily acceptable to the temper of our culture, a freedom of attitude that might acquiesce in the inconsistencies of Ruskin but could not flourish under the system of Fry'.

Ironside was largely responsible for the re-awakening of 'serious' interest in Burne-Jones - without which John Christian's work would never have been possible. Together with John Gere, Ironside also compiled the Phaidon Press volume, Pre-Raphaelite Painters, which appeared in 1948, on the centenary of the foundation of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. This book marked the beginning of the end of twentieth- century obscurity for the Pre-Raphaelites. One of the more singular features of contemporary cultural life since the second world war has been the seemingly unbounded efflorescence of interest in Romantic painting (vide the return of Francis Danby), and specifically in Pre-Raphaelitism among a large section of the public interested in the visual arts.

And yet advanced 'Modernist' opinion has remained sceptical and unconvinced. In 1944, Clement Greenberg, the architect of the new formalist criticism in the USA, wrote dis- missively about the latest 'romantic revival' in painting and poetry, in both Britain and America. Opposition to Romanticism was a central plank of his early position. Greenberg wrote that the new interest in, as he called it, 'Pre- Raphaelism', and the literary aspects of painting, stood historical Romanticism on its head. For this new Romanticism

does not revolt against authority and constraints, but tries to establish a new version of security and order. The 'imagination' it favors seems conservative and constant as against the 'reason' it opposes, which is restless, disturbing, ever locked in struggles with the problematical. 'Reason' leads to convictions, activity, politics, adventure; 'imagination' to sentiment, pleasure and certainties. The new 'Romanticism' gives up experiment and the assimilation of new experience in the hope of bringing art back to society, which has itself been 'romantic' for quite a while in its hunger for immediate emotion and familiar forms. A nostalgia is felt for a harmony which can be found only in the past and which the very technical achievements of past art seem to assume.

This sort of view has persisted. Quentin Bell has described how, even in the late 1960s, he had great difficulty in persuading his colleagues and his students of the validity of his interest in the Pre-Raphaelite movement; and only three years ago, John Berger - as it happens disingenuously - asserted the reason he had broken off relations with me was because of my interest in Pre-Raphaelitism.

These sorts of unquestioning, fashionable Modernist views were entrenched in, say, the rhetoric which surrounded the exhibition British Art in the 20th Century: the Modern Movement, which was held at the Royal Academy in 1987. It is that rhetoric which John Christian was determined to challenge. 'Old ideas,' he writes, 'die hard, as we saw in the exhibition ... at the Royal Academy in 1987. Here again, with the single exception of Eric Gill, there was no overlap with our exhibition other than in the Slade area.'

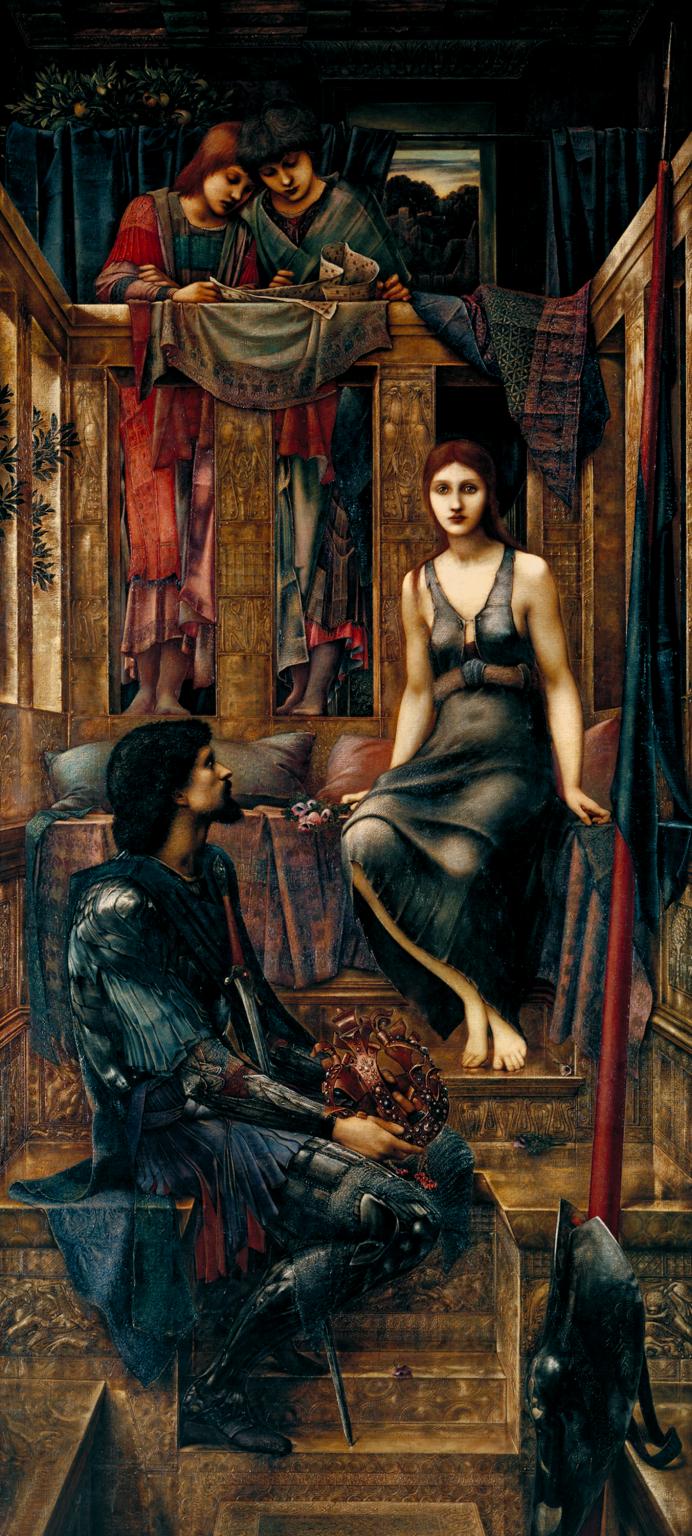

So did Christian succeed in offering an alternative view of British art to that provided by Norman Rosenthal and his colleagues at the Academy? On the surface, the answer to that must be a resounding 'no'. Christian is, of course, a scholar of Burne-Jones, and was responsible for an exemplary exhibition of Burne-Jones's work at the Hayward Gallery in 1975. It was therefore disappointing to discover that Burne-Jones himself was so poorly represented in the Barbican show - Vespertina Quies is hardly the masterpiece of his later years. Minor, and less than minor, works by Burne-Jones's followers and studio assistants were also allowed to proliferate. The Last Romantics was cluttered with Birmingham Pre-Raphaelites; academic revivalists of Pre-Raphaelite genres, like Frank Dicksee and John Waterhouse; fey fairy painters; Viennese-inspired pictures by Charles Ricketts and Charles Shannon; illustrators of the Celtic fringe; and even with neo-classicists, from the British School in Rome in the 1920s.

When all is said and done, there was but one room of outstanding paintings and drawings in the show, namely by those painters whom Christian calls 'Slade School Symbolists', that is, artists who studied at the Slade just before the first world war, like Stanley Spencer, Paul Nash, Mark Gertler and David Bomberg. As Christian himself points out, these painters also featured prominently in the Royal Academy exhibition, where they were rightly and powerfully presented as among the century's greatest British artists.

And so, it must be admitted that the Barbican exhibition presented us with very little of real stature which had not also been represented in the Academy show. But the Academy exhibition also contained more than its share of phoney nonsense - especially in the rooms chronicling art from the 1950s to the present day. I would argue that, say, Richard Hamilton's Towards a definitive statement on the coming trends in men's wear and accessories (c) Adonis in Y-fronts, 1962, is, roughly speaking, the 1960s equivalent of John William Waterhouse's slick and facile, Echo and Narcissus, 1903, included as an academic Pre-Raphaelite picture in Christian's show. (In fact, I much prefer the Waterhouse to the Hamilton. Seen 'in the flesh', Waterhouse's painting demonstrates verve and immediacy. Hamilton's necrophiliac touch and techniques always snuff out every semblance of life.)

Or take Stuart Brisley's Survival in Alien Circumstances, 1977- 81. To my mind, this silly and sentimental work - pv 'tographs of the two weeks Brisley spent splashing about masochistically in the water at the bottom of a deep hole - is the contemporary equivalent of, say, Herbert Draper's set-piece, The Golden Fleece, which shows Jason in mortal peril on the high seas. Brisley and Draper are both institutional artists who have made use of fashionable techniques to trigger spurious emotions. Similarly, Gilbert and George's Wanker, Prick Ass and Bummed of 1977, can be compared, in their vacuity and vulgarity of feeling, to Frank Dicksee's Chivalry, which shows a knight, literally in shining armour, about to rescue a distressed maiden tied to a tree, in delectable disarray.

My point is that objections which Greenberg addressed to 'romantic' art in the 1940s, now apply much more aptly to Modernist art, the institutional art of our own time. Today, of course, it is Modernism which has given up 'the assimilation of new experience in the hope of bringing art back to society', which, we might add, has itself been 'modern' for quite a while in its hunger for immediate emotion and familiar forms.

The second, and to my mind more important point that needs making about the Academy show is that, the breathy rhetoric of the catalogue notwithstanding, much of the work on exhibition there in fact owed little to the Modern movement. To be more exact, many of the outstanding British artists of this century have simply incorporated elements of international Modernism into their work as a way of furthering their Romantic concerns. Some have not even bothered to do that.

Take the case of Stanley Spencer who was represented at the Academy by six paintings, and at the Barbican by two. At least one of the latter, Zacharias and Elizabeth, 1914, is, in my view, a masterpiece. And yet everything about it involves an appeal, over the heads of both the academic Pre-Raphaelites and the insipid followers of Burne-Jones, to the attitudes of mind of Pre-Raphaelite painting in the mid-nineteenth century. Spencer was everything that - according to the Modernists - the twentieth-century artist ought not to be, and yet he was undoubtedly one of the greatest British artists of the twentieth century; far greater, I believe, than Francis Bacon. Spencer was narrow-minded and provincial; a man of biblical, rather than scientific vision; concerned with the past, rather than the future (which he conceived in terms of a second coming); an enemy of industrialisation, indeed of almost everything about the modern world. Spencer looked at nature with the intensity and longing of one who believed that he could find God there. [See plate 9b.]

Now one could say that such attitudes were what Fry and Bell sought to dismiss when they castigated Pre-Raphaelitism. (Although their antipathy to Englishness was perhaps stronger than their affiliation to Modernism, which was one reason why they responded to a thorough-going French Symbolist painter like Gauguin.) Fry could not, however, dismiss Spencer: he had too sharp an eye for that. He included him in the first Post- Impressionist exhibition.

For many Modernists who came after, one way of dealing with Spencer was to argue that he was 'unique' - a freak if not of nature, then of cultural life, who stood outside the laws of his time. But John Christian shows this just was not true. Spencer belonged to a tradition, a Romantic and Pre-Raphaelite tradition - an English 'Post-Impressionism'.

As I try to argue in my book, Theoria, what was true of Spencer was true of a remarkable number of our greatest contemporary artists. Certainly, many of them recognised the pictorial failures of Pre-Raphaelitism, but they admired the desire of the Pre- Raphaelites, and of Turner before them, to paint pictures which were rooted in an imaginative and spiritual response to the world of nature.

Paul Nash, for example, begins with an admiration for Rossetti. The experience of the 'godless' landscapes of the first and second world wars reunites him with the earlier and tougher vision of Holman Hunt's Scapegoat and paves the way to his own luminous last landscapes, surely some of the greatest Romantic paintings since Palmer. Similarly, as I have argued at length elsewhere, Bomberg's search for 'the spirit in the mass', or Henry Moore's sculptural preoccupations, stand in direct and undeniable continuity with the aesthetic concerns of the nineteenth century. Both realised that the imaginative world of the arts necessitated, at the very least, a 'suspension of disbelief'. Whatever philosophy they may otherwise have espoused in the real world, in the illusory spaces of their art, these artists were vitalists rather than materialists. They were motivated by the desire to see beyond appearances, to depict the spiritual essences of things.

Greenberg had a sharper eye and a much finer critical mind than either his acolytes or his critics, and yet it seems to me that he was wrong on the most fundamental issue of all, when he argued that 'the highest aesthetic sensibility rests on the same basic assumptions ... as to the nature of reality as does the "advanced" thinking contemporaneous with it'.

In Britain in the twentieth century our greatest artists have invariably shown a refusal of modernity, an unashamed preference for an older, romantic and spiritual tradition. This was also indubitably true of much of the best French painting, especially after Impressionism. (I write this as someone who himself remains an atheist and a materialist.)

John Christian's show fell apart because he included so much empty and academic work in which the high ideals of the Romantic movement were replaced by slickness, commercialism, or imaginative ineptness. He also omitted much of real stature. Why, for example, were there no paintings by G. F. Watts, at his best a great, and unjustly neglected artist, whose work foreshadowed so much of what is best in the British achievement in the twentieth century?

Exactly the same criticisms can be raised against Norman Rosenthal and his colleagues at the Royal Academy. They, too, misunderstood the nature of the tradition with which they were dealing. Neither Christian nor Rosenthal have Baudelaire's understanding of what it was that made British art unique both in the last century, and, I believe, in our own. (Can it be an accident that both overlooked the work of Cecil Collins which was, I felt, triumphantly vindicated at his retrospective exhibition at the Tate, in May 1989?) In 1859, Baudelaire regretted the absence of a long list of British artists from the French salon, describing them as 'enthusiastic representatives of the imagination and of the most precious faculties of the soul'. Once, British art seemed hopelessly inferior to that of France. Yet, today, the British school is probably the liveliest and most creative in the world and French painting is nowhere.

1989