This February, my script MODERN ART based on the life and times of Peter Fuller, will be participating in the Screenplay Awards for Hollywood Reel Independent Film Festival 2020. This process has allowed me to have a conversation and a relationship with the father I never knew. In many ways this is a humanitarian experiment. Our faith and doubt in the true purpose of modern cinema and the arts in the modern world, as either a commodity or a consoling spiritually uplifting engagement, or both, is at the centre of MODERN ART. A historical piece this size has been a very challenging endeavor, there’s so many people involved and so much at stake, being at the centre of it has pushed me to develop in all sorts of ways, as an artist and as a human being. I hope in that sentiment that I stand for each audience member and each reader of this script, we need this story, now more than ever. To celebrate this event I will be posting an article by Peter Fuller everyday on my blog through the month of Feb. starting with The Journey which was the last article my father published and details what has been called “One of the top 5 most extraordinary things about the 1980s art world” - The Sunday Telegraph, Peter Fuller’s change of mind and his personal pilgrimage towards the spiritual in art. This took him deep into the heart of Modern culture and it’s players, the intellectuals, artists dealers, collectors and administrators of the art world and it’s machinations. A fascinating and illuminating read unlike much else written in the last hundred years. I felt this was the right piece to be the first of many detailing Peter’s adventures, and served like an introduction. I hope you enjoy and subscribe on the right to receive updates!

The Journey

by Peter Fuller

I hope that I will not sound unnecessarily cussed if I begin by saying that I regard the exhibition, The journey, with unease and even rank scepticism. At the time of writing, I have not seen any of the works which will be on show, but, with a few notable exceptions, the list of names of those artists who are taking part does not inspire much confidence in me. I am aware that this sounds arrogant and, no doubt, discourteous to the artists concerned, but then serious criticism is often that way. After all, such criticism is itself the result of a personal 'journey'. As it happens, I agree with Gilbert, one of the contributors to Oscar Wilde's famous dialogue, The Critic as Artist, who argues that higher criticism is 'the record of one's own soul'. He goes on to describe it as 'the only civilized form of autobiography, as it deals not with the events, but with the thoughts of one's life; not with life's physical accidents of deed or circumstance, but with the spiritual moods and imaginative passions of the mind'.

Before I spell out my objections to The Journey, I want to say something about how I arrived at such a view of criticism. I have written often enough about how I grew up - in an intellectual sense, at least - at a time when materialism of one kind or another was the orthodoxy in critical theory. In the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s, 'serious' critics invariably seemed to pride themselves on the thoroughness with which they renounced the idea of the transcendent in art. Words like 'soul', 'grace', 'spirit' and even, unbelievable as it now seems, 'imagination', were taboo.

At that time such an intellectual ambience was congenial to me - not least because I was reacting against the somewhat claustrophobic religious atmosphere I had inhabited as a child. Inevitably, I was drawn towards the intellectual ambience of Marxism, then a great deal more prevalent and persuasive in Britain than it is today. Indeed, it was among Marxists that I acquired much of my aesthetic education.

John Berger was, in an unofficial sense, my teacher in criticism. In his book, Ways of Seeing, he associated aesthetic valuing with 'bogus religiosity'. As far as he was then concerned, the spiritual dimension of art was an anachronism, a sort of penumbra of the function of art as property and in the market-place. Berger had, of course, nailed his colours to the mast of 'Realism', but almost all the rival theories of art also presented themselves as thorough-going materialisms. Indeed, Formalists, Structuralists and Post-Structuralists alike justified their respective viewpoints on the grounds that they were more materialist than those of the next man, or very occasionally, woman.

I cannot claim to have been an exception. My early books on art were also attempts to elaborate a materialist aesthetics. In Beyond the Crisis in Art, I drew what I could from sociological and political theory. To this day, this is the only one of my books which has ever been regarded as even worthy of attention by the Left. It amuses me that there are critics such as John Roberts, who, in a recently published book called Postmodernism, Politics and Art, argue with the texts in Beyond the Crisis in Art as if they contained my final positions. Roberts simply isn't prepared to entertain any greater doubts about left-wing theories of art than the modest questionings of that early book.

Marxism, of course, endeavoured to see every aspect of human culture as determined exclusively by historical circumstances. But, in my own writing about art, I was already beginning to emphasise the relative constancy of the human body, indeed, of the human being itself, from one historical moment to the next. Nothing propelled me in that direction faster than my belief in the universality of great art. I brooded upon the fact that the greatest works of art transcend those moments of history in which they were made and appear to 'speak' directly to those who lived in quite different historical circumstances. The explanations offered by Marx and the Marxists for this seemed to me inadequate - special pleading of the least convincing sort. I can still remember with what excitement I read Herbert Marcuse's posthumously published essay, The Aesthetic Dimension, in which he assailed orthodox Marxist aesthetics. 'By virtue of its trans-historical, universal truths,' he wrote, 'art appeals to a consciousness which is not only that of a particular class, but that of human beings as "species beings", developing all their life-enhancing faculties.'

Marcuse wrote that 'art envisions a concrete, universal humanity (Menschlichkeit), which no particular class can incorporate, not even the proletariat, Marx's "universal class" '. Such ideas struck a receptive chord in me. My own book, Art and Psychoanalysis, plunged into a terrain which was simply out-of-bounds for orthodox Marxist aesthetics. I explored psychoanalytic ideas, especially those of the British School of 'object relations' analysts, in an attempt to say something about the pleasure, wonder and mystery which I derived from the experience of art. In particular, I was interested in the possibilities of psychoanalytical understanding of form itself. In The Naked Artist I tried to take these ideas still further and draw upon natural history and biology too.

Nowadays, despite having changed my views on many of the ideas of these books, I would not disown any of them. Art and Psychoanalysis still commands a steady readership and has been translated into Portuguese, Greek and Chinese. Therein I argue that the formal dimensions of painting are themselves symbolic. Although this will seem perfectly obvious to anyone with psychoanalytical experience, it is hardly common currency in the art world, even today.

Black In Deep Red, by Mark Rothko, 1957

Nonetheless, I came to believe that Art and Psychoanalysis was imperfect and partial. The great New Testament scholar, Rudolf Bultmann, once complained about the way in which modern theology had ended up with a 'God-shaped hole'. It seemed to me that deconstructive and semiotic approaches to art criticism had disappeared into an 'art-shaped hole'. But was my own brand of materialist criticism bringing me any closer to the palpable and yet mysterious presence of art itself? I could describe the 'psychodynamics' which informed a Rothko painting, but my critical vocabulary could not say much about the hair's breadth which divided one of Rothko's successes from his most abject failure. Was that vocabulary worth having at all? I came to feel that all I had written failed to give any explanation of the central question of evaluation in our response to art.

There was only one critic who called himself a Materialist who seemed to be grappling with this vital aspect of aesthetic experience, and that was Clement Greenberg. This is not the place to enter into any detailed discussion of the influence which he has had over my development. Suffice to say that I regard him as, without doubt, the greatest critic of art that America has produced or is ever likely to produce. I have nothing but contempt for his detractors. Invariably they rail loudest against those aspects of Greenberg's taste for which I have the greatest admiration, especially his willingness to test irony against judgement.

The irony, for me, is that I cannot agree with all, or even with many, of the specific evaluations Greenberg has made. For example, when I visited him in 1989, he was insisting that Jules Olitski was the greatest living painter. I have never seen a painting by Olitski which I regard as major, and I find his recent pictures vulgar and tasteless. Yet I continue to admire Greenberg because he has the courage of his aesthetic and moral convictions. He knows that the values which great art proposes are trans-historical. He understands that taste is the only means we have for the apprehension of such values, and he realises that individual taste itself is never invested with the authority of those absolutes in whose name it aspires to speak.

If, in the end, I found myself parting company with Greenberg too, it was because his approach seemed to me to be positivist, by which I mean that he assumed that there was nothing more to aesthetic experience than that which is immediately given to the senses. I realised that, if this was true, then the sort of emotion to which a beautiful red scarf gave rise in me would be indistinguishable from that which I felt when contemplating the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

The simplest way of describing the changes which took place in my taste from about 1979 onwards, would be to say that I developed an ever-deeper sympathy for the Romantic, the Gothic, and the spiritual dimensions of art. I have read that the reason for this was my growing interest in the writings of Ruskin, but I am not sure that this is true. Indeed, I think that I became ever more involved with Ruskin because my taste was changing anyway.

For example, I developed a passionate interest in the great Gothic cathedrals and the medieval parish churches of Suffolk, where I acquired a cottage in 1981. It seemed to me that no 'materialist' culture - certainly not the high Modernism celebrated by Clement Greenberg - had ever remotely approached the aesthetic glories of these churches. I was very much aware that their splendours and their intricacies were dependent upon a faith which I could not share and which was not even shared by contemporary Christians. Although the Catholic Church in post-second world war Britain might inspire a building as shoddy as Liverpool's Catholic Cathedral, it could never give rise to the harp-playing pigs and evil old women which spring up from the early fifteenth-century bench-ends in Stowlangtoft church.

When, in the early 1980s, I wrote the essays gathered together in Images of God, I felt that I was being tremendously daring and even perverse in reviving the idea that aesthetic experience was greatly diminished if it became divorced from the idea of the spiritual. What I responded to in Ruskin, above all else, was the distinction he made between 'aesthesis' and 'theoria', the former being merely a sensuous response to beauty, the latter what he described as a response to beauty with 'our whole moral being'. My book, Theoria, was an attempt to rehabilitate 'theoria' over and above mere 'aesthesis'. I also tried to communicate my feeling that the spiritual dimensions of art had been preserved, in a very special way, within the British traditions.

In my critical writing I came to emphasise how British artists appeared to have faced up to the aesthetic consequences brought about by the spiritual dilemmas of the modern age. In particular, I became interested in the links between natural theology and the triumphs of British 'higher landscape', and those beliefs about nature as divine handiwork which were held with a peculiar vividness and immediacy in Britain.

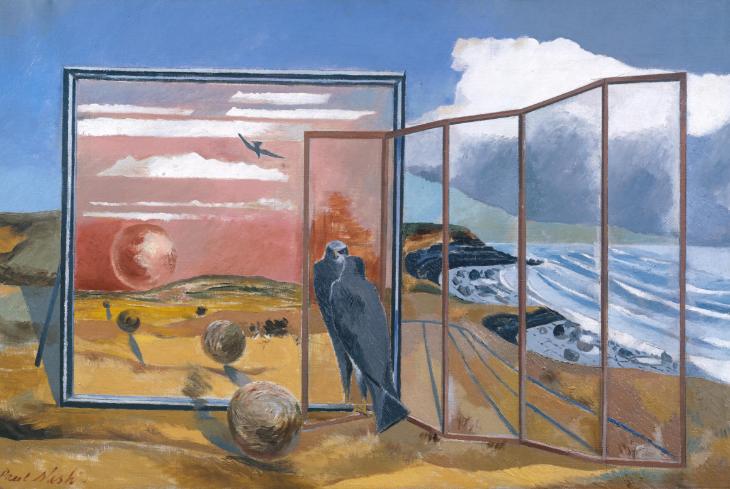

The experience of Matthew Arnold's 'long-withdrawing roar' of the Sea of Faith, and the exposure of 'the naked shingles of the world' created a great crisis for art, as for every other dimension of cultural life. However, the best British artists of the twentieth century faced up to that spiritual crisis. I interpreted the work of David Bomberg, Paul Nash, Stanley Spencer, Henry Moore and Graham Sutherland as differing responses to the phenomenon of 'Dover Beach'. I argued that all these artists were imperfectly modern, and that this imperfection was a source of their strength. Unlike true Modernists they did not deny the spiritual and aesthetic calamity brought about by the ever-present weight of God's absence. They did not merely tease aesthesis, but appealed to theoria, regardless.

When I first put these ideas forward, they seemed to me to be very much against the grain of the times. After all, the 1980s witnessed a terrible debasement of art. I have often enough described how, in the 1980s, a kind of Biennale Club Class Art took over in the art institutions and smothered any real response to the strengths of our national tradition. The decade saw the rise of rampant commercialism of a crassness and vulgarity never before encountered. Sadly, many younger artists turned to the anaesthesia of the mass media rather than the world of natural form for inspiration. At times, it seemed as if there was a general indifference to aesthesis, let alone theoria.

Of course it was not as simple as that, nor was I so alone in my tastes and views as I sometimes felt. I began to realise that the very baseness of the decade has created a counter-current of reaction. One instance of this was the resurgence of interest in the work of a painter such as Cecil Collins. Another was the great number of painters of real calibre who insisted upon pursuing higher landscape, regardless of art world fashions. They were, unsurprisingly, very much in tune with the wider 'ecological' concerns of the day. Everyone, it seemed, except the art world, was insisting upon the need to re-create an imaginative and spiritual response to the world of nature.

I am sure that, in retrospect, the 1980s will be seen as a period almost as rich in visionary landscape painting as the 1940s. Just look at the work of some of the older painters such as Norman Adams or John Piper; or take the work which Adrian Berg, Maurice Cockerill, Christopher Cook, Maggi Hambling, Derek Hyatt, David Leverett, Terry Shaves, Len Tabner and William Tillyer did in the 1980s. What a pity that not one of those artists was included in The Journey.

Equally exciting for me was the discovery that criticism too was beginning to emerge from its 'dark night of the soul', regardless of the fact that for much of the decade the dreary progeny of the 1960s continued to rule the roost. What a baleful influence was exerted over criticism of both literature and art by figures such as Norman Bryson, T. J. Clark and, worst of all, Terry Eagleton. The art institutions and magazines, academic art history and journalistic criticism alike became dominated by modes of 'discourse', which obscured the view of pictures and sculptures as art. Indeed, the dark shadow of cultural materialism seemed to hang heavily over any attempt to revive interest in the only dimensions of art which counted for anything at all - those of aesthesis and theoria.

As the decade came to a close, all that began to change. In large part, I am sure, events in Eastern Europe, and indeed throughout the world of organised Communism, contributed to the shift of critical emphasis in the West. Quite quickly, Marxism, and indeed historical materialism itself, began to lose whatever claims they may have once possessed over ethical and aesthetic life. The foundations of much of the 'higher criticism' of the 1980s were shown to have been built on sand.

For me, one of the most important books of recent years has been George Steiner's Real Presences, a bold essay in which he argues that the chatter of secondary discourse - whether academic or journalistic - is just a defence against an encounter with that real presence which great art has to offer. Steiner argues that even in a secular culture such as ours, great art is necessarily 'touched by the fear and ice of God'. He affirms that even, or perhaps especially, in an era of unbelief the artist must make 'a wager on transcendence'. Needless to say, these words had great resonance for me.

But not all recent talk of the transcendental dimension of art has been as convincing as Real Presences. Almost every day, it seems, we receive further news of an escalating 'spiritual revival'. The Journey is only the latest in a swelling spate of books, seminars, conferences and other projects on some aspect of the transcendental experience in art. My own scepticism dates back at least three years, to the exhibition, The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890-1985, which was held at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1987. In this show a whole range of erstwhile American Modernists - deeply implicated in the reduction of art to the vulgar materialism of Pop or the sterile vacuity of Minimalism - were rehabilitated as founders of the new spirituality. Examples of every sort of foolishness from the recent history of art were suddenly kitted out with new 'transcendental' critical robes. As usual, much of the best art of our time, including every one of the British painters and sculptors I have referred to above, was ignored altogether.

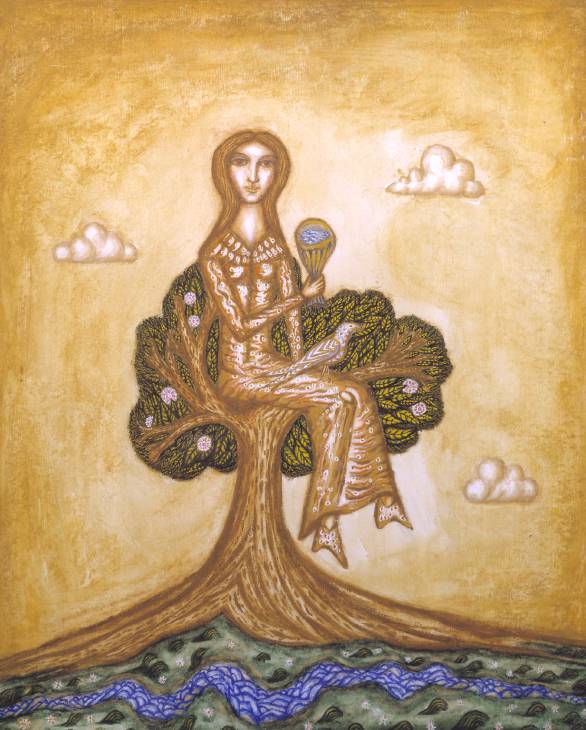

Cecil Collins, The Artist's Wife Seated In A Tree, 1976

The late Cecil Collins told me, more than once, of his own mixed feelings about the revival from which his own reputation so greatly benefited. Cecil, too, was sceptical about the loose and superficial invocation of the terms 'romantic', 'visionary' and 'spiritual'. Here in England, I believe that exhibitions like A Spiritual Dimension and New Icons have only served to exacerbate the problem. While there was some good work in both shows, there was also much which was merely fashionable, sentimental or worse. The truth is that very little in either of these exhibitions could be said to be touched by 'the fear and ice of God'. Chatter about transcendence is not qualitively different from chatter about the framing edge, 'proletarianisation', signifying practices or post-modern radical eclecticism. Indeed, the appropriation of the language of the spiritual to defend work which is trivial or banal, is perhaps the saddest twist in the present-day shrouding of the transcendent potentialities of art. My heart sinks, for example, when I hear my friend Sister Wendy Beckett defending the reductionist ethic of Minimalism.

Peter Fuller, Stephanie Burns, Sister Wendy Beckett

It is now more than seventy years since Rudolf Otto wrote so revealingly in The Idea of the Holy, about the part played by the void, or emptiness, in Chinese painting. We could understand this, Otto believed, through a comparison between the 'nothingness' and the void of the mystics and the enchantment and spell exercised by 'negative hymns'. 'For "void",' he wrote, 'is like darkness and silence, a negation, but a negation that does away with every "this" and "here", in order that the "wholly other" may become actual.' It seems to me that there is every difference in the world between this spiritually replete emptiness and the numbing vacuity of works by artists such as Carl Andre, Agnes Martin, Ellsworth Kelly or Brice Marden.

The trouble with so much recent art and criticism of the spiritual revival is that it has got hold of a new, and these days increasingly trendy, way of talking about art. Spiritual terms are deployed regardless of whether the art in question has struck that perilously risky 'wager on transcendence' or not. No attention at all is paid as to whether the wager has actually been won.

In 1989 I contributed to the colloquium, 'The Church and the Visual Arts today: partnership or estrangement?', organised at Winchester Cathedral by Canon Keith Walker. I was appalled to see men of the church apparently nodding in agreement when a member of the staff of the Tate Gallery encouraged them to believe that Gilbert and George and Andy Warhol were among the greatest spiritual artists of our time. I had a vision of lurid stained glass windows with titles like Marilyn and Dick Seed rising above the altars of parish churches and cathedrals throughout the land.

When my turn came to speak I tried to tell the assembled clerics about the ethical, aesthetic and spiritual bankruptcy of the institutions of contemporary art. I argued that it was up to the churches to rehabilitate the idea of the transcendent in art. It was not their task to condone the ubiquitous symptoms of anaesthesia and spiritual bankruptcy which pass for art in the modern world. I don't think my words counted for much. In fact my worst fears seem to be coming true much sooner than I expected.

Richard Long, Lincoln Cathedral

It is, I believe, a tragedy that consideration was given to inviting an artist such as Richard Long to create a piece within Lincoln Cathedral. His work, for me, is symptomatic of the loss of both the aesthetic and the spiritual dimensions of art. He shows little trace of imagination, of skill, of the transformation of materials. Seen in contrast to the greatest achievements of the British tradition in art, Long's relationship to the world of nature is simply regressive. His work is sentimental and fetishistic. By contrast, 'the Cathedral of Lincoln,' as Ruskin once wrote, 'is out and out the most precious piece of architecture in the British islands, and - roughly - worth any two other cathedrals we have got'. It is the greatest monument this country possesses to what, in aesthetic terms, can be achieved through work, faith, worship and praise. Elsewhere Ruskin proclaimed:

Go forth again to gaze upon the old cathedral front where you have smiled so often at the fantastic ignorance of the old sculptors: examine once more those ugly goblins, and formless monsters, and stern statues, anatomiless and rigid; but do not mock at them, for they are signs of the life and liberty of every workman who struck the stone; a freedom of thought, and rank in scale of being, such as no laws, no charters, no charities can secure; but which it must be the first aim of all Europe at this day to regain for her children.

Richard Long's chips and pebbles are evidence that she has not yet done so. Claims that his work is worthy of 'spiritual' attention are preposterous, but they do not surprise me. 'What I affirm,' writes Steiner, 'is the intuition that where God's presence is no longer a tenable supposition and where his absence is no longer a felt, indeed overwhelming weight, certain dimensions of thought and creativity are no longer attainable.' Under these circumstances, there is perhaps nothing to be done except to fall back on the consolations of lost illusions, in art, if not in faith. These we can find more readily in the ancient fabric of the west front of Lincoln Cathedral itself, than in anything an artist like Richard Long may place within it.

Peter Fuller 1990

Peter Fuller's gravestone in Stowlangtoft, sculpture by Glynn Williams