A new exhibition by William Tillyer opened May 1st at Bernard Jacobson Gallery:

The Palmer paintings continue Tillyer’s long engagement with the English landscape and in particular his lifelong obsession with clouds. The Palmer of the title is Samuel Palmer 1805-81 the visionary British Romantic landscape painter who, like Tillyer, had an almost mystical view of man’s relationship with the landscape and who has long been an influence and inspiration for Tillyer. (The subtitle is from a line from Psalm 65:11).

Abstracted dreamlike cloudscapes bathed in a golden light, these paintings combine Tillyers’s Romantic as well as his materialist sensibilities. The paintings are produced using a unique technique whereby Tillyer pushes acrylic paint through a fabric mesh that he hangs from the ceiling of his studio. Working from behind as well as from the front he gives a third dimension to his painting, breaking through the grid-like picture plane implied by the mesh and into the real world.

This made me look back on my father's connection to Tillyer's work. The first thing that came to mind was the famous debate with Matthew Collings on the Late Show, not long before he died. This was pre-YBA's when my father was championing aesthetic painting and a Neo-Romantic revival seemed all too possible. Each critic could choose five works of art, and had one minute to make their case for each, before the camera turned over to the other. My father was championing aesthetic painting, as he so fervently did in his magazine Modern Painters and Matthew Collings was championing avant-garde art. One of the five pieces my father chose was a watercolour by William Tillyer. I cannot show the debate in full here, but here is the one minute clip where he discusses Tillyer's painting.

It didn't take long to come across his essay on Tillyer in 1987 first published in Modern Painters and in the catalog for the exhibition of 200 watercolours at Bernard Jacobson Gallery in 1987.

William Tillyer and the Art of Water-Colour

Nothing frightens a modern painter more than the challenge of exterior appearances. Sooner or later he will have to find a mode of 'study', a means of communing direct with nature. When this moment arrives we shall see the re-birth of landscape painting and portraiture.

Patrick Heron, The Changing Forms of Art, 1955

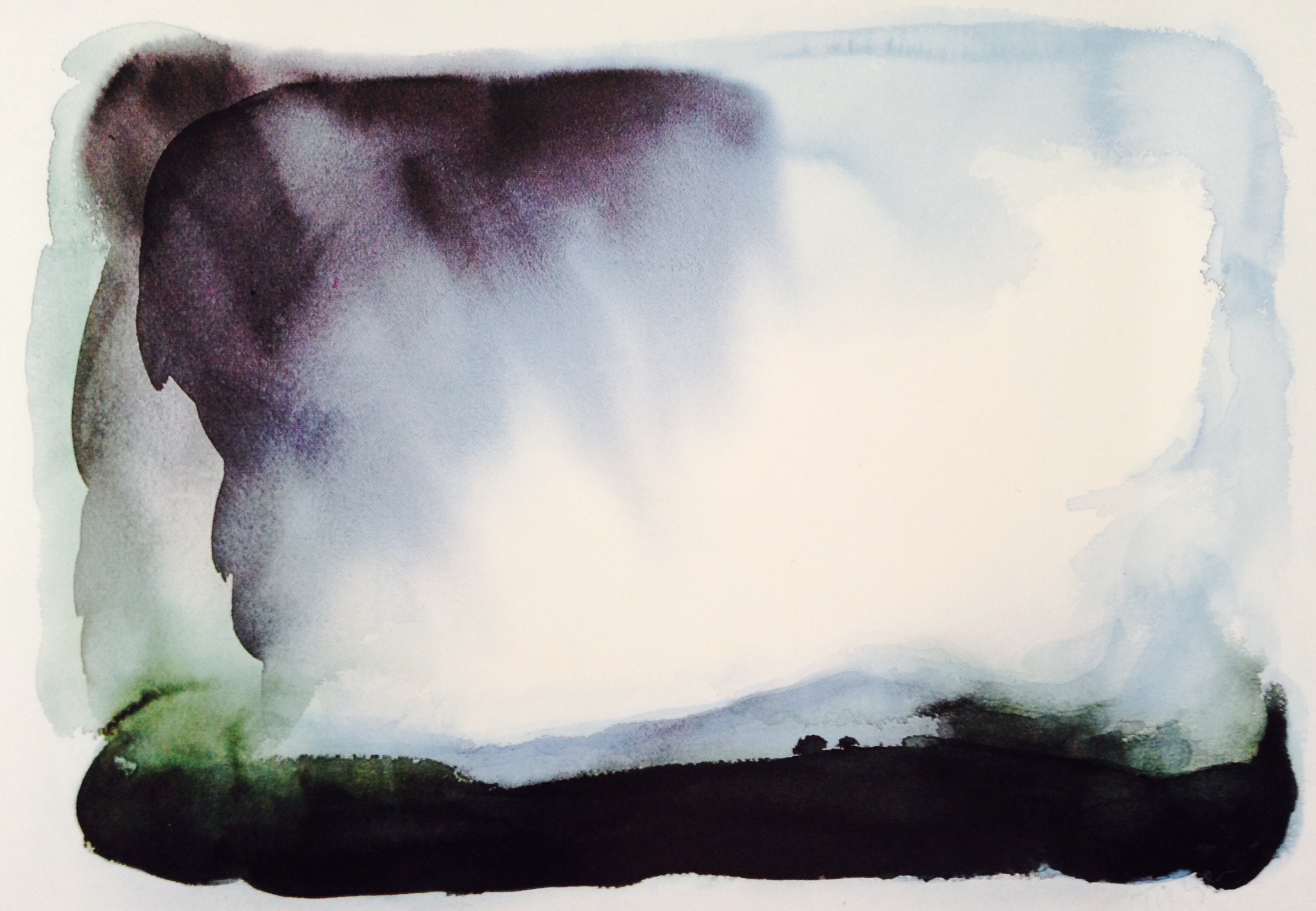

The North York Moors, falling sky

Contemporary art criticism is notoriously wary of that which cannot easily be pigeon-holed. William Tillyer's work has received less attention than it deserves because he draws upon two quite different traditions. He breaks the conventions of both, and so seems to belong to neither.

Tillyer's paintings depend, for their aesthetic effects, upon his responses to the world of nature, but his pictures do not offer a reproduction of the appearances of that world. Indeed, they seem to be deeply involved with questioning the nature of the medium itself - a typical late Modernist concern. Tillyer's painting in oils shows a characteristically self-critical doubt about the validity of illusion and representation, and a restless preoccupation with the nature of the picture plane, the support and the framing edge. Tillyer often seeks 'radical' solutions, assaulting the surface, tearing, reconstituting and collaging.

Although Tillyer's water-colours - my principal concern here - invariably spring out of his response to particular places, they are in no sense topographic. Indeed, we might imagine Tillyer making the same retort as his predecessor, David Cox, when the committee of the Water-Colour Society criticised the vagueness of certain of his paintings. 'These,' wrote Cox, 'are the work of the mind, which I consider very far before portraits of places.' Instead of trying to tell us what a scene looks like, Tillyer seems to be engaged in a search for what Roger Fry called 'Significant Form'; that is, for 'lines and colours combined in a particular way, certain forms and relations of forms' which arouse aesthetic emotions through formal means. Yet Tillyer's water-colour paintings are not abstractions, even though their relationship to the visible world of nature may be oblique.

Vale of Pickering, North Yorkshire.

'Good water-colour drawings,' wrote John Ruskin, '. . . are pleasant to everybody. Not so pleasant as bad ones to the general mob; but never offensive, and in time attractive.' Tillyer's best water-colours are not only good, they are also exceedingly pleasant and attractive. When I look at a great one like, say, The North York moors, falling sky [see plate 12b], I find that my eye is drawn easily into its shimmering veils, membranes and pools of pure, vibrating blue. And yet, in terms of critical response, this visual seductiveness has hardly worked in Tillyer's favour. One of the legacies of the recent history of painting is a belief that 'serious' art must be 'difficult'. It ought not to please too easily. Instead, the viewer should feel affronted, or at least offended. In this critical climate, watercolour has tended to be regarded as the choice of amateurs, Country Life readers, members of the Old Water-Colour Society and other aesthetic recidivists or dilettantes. Water-colour is 'not serious'.

Here, however, I wish to argue an alternative view, for I believe that water-colour possesses possibilities which other media do not. When fully realised, these delicate qualities touch upon some of the most intimate and nuanced dimensions of aesthetic experience. Moreover, I believe that Tillyer has not only mastered the potentialities of this subtle medium, but has also developed them in a thoroughly original way.

Water-colour, as a substance, is simply pigment ground up with a water-soluble gum, like gum arabic. Such techniques are very ancient. The Egyptians used them, and so did the illustrators of medieval manuscripts. In more recent times water-colour has been displaced by the more gestural, durable and theatrical properties of oil-based paints, and has survived largely as a secondary medium. For example, some painters would enhance their preliminary studies in ink or pencil with monochrome sepia washes. Alexander Cozens, an artist to whom Tillyer appears to owe much, was perhaps the first to see how water-colour presented an opportunity for imaginative expression which other media did not. He developed a system for inventing imaginary or ideal landscapes from washes and 'blots'.

When the full range of hues returned in eighteenth-century England, this was due to a vogue for drawings of Gothic ruins and other architectural features. Water-colour provided a quick and convenient way of tinting these studies. But the history of art is full of examples of processes and materials being developed, or revived, for 'functional' reasons, then revealing quite new aesthetic and imaginative possibilities of their own. (Etching is another good example. It was originally developed as a convenient, if rude, means of reproduction.)

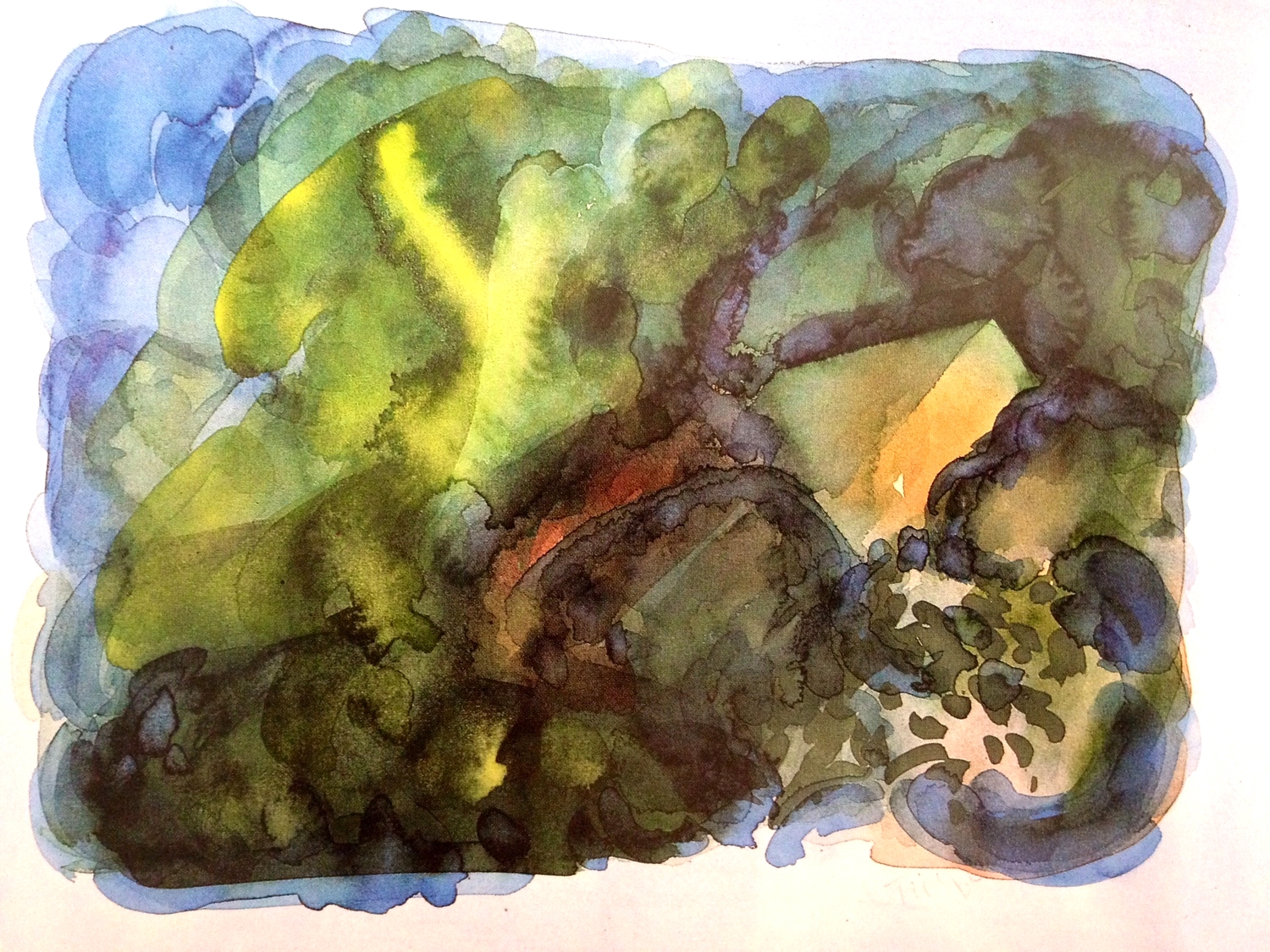

Yorkshire, Great Fryup Dale.

I am sure that art historians know better, but I like to think that the awakening to the possibilities of water-colour occurred in Dr Thomas Monro's workshop, where Girtin and Turner worked alongside each other filling in the skies on architectural and topographic drawings. Was there a moment when Girtin suddenly came to feel that his living pools of colour contained more trembling aesthetic potential than the illustrations and reproductions to which he was applying them? At least he must have wondered whether more immediate and sensuous responses to the world of nature might not embody spiritual values as significant as those found in the detailed, linear depictions of the relics and ruins of medieval Christendom, at which he and Turner were so proficient.

It was not immediately clear what contribution water-colour might make to this emerging landscape aesthetic. The early practitioners were often successful in forcing the medium to do that which did not come 'naturally' to it. Ruskin recommended the use of 'body colour', or water-colour mixed with white to make it opaque, like gouache. Turner liked to enhance textures and effects by roughing and scraping the surface of the paper. David Cox, too, rubbed, scrubbed, scratched and sponged. In the hands of these masters, such techniques often led to works of undeniable richness and strength, but they are rarely recommended by teachers of water-colour today.

It was, perhaps, Girtin who first sought to 'purify' the practice of water-colour, and, in a rather 'modern' way, endeavoured to isolate that which was peculiar to his chosen medium. Girtin transformed the practice of water-colour. He abandoned the idea of monochrome underpainting. He made use of thick, off-white cartridge paper, and relied increasingly upon the whiteness of the surface instead of added highlights or body colour, to indicate areas of heightened light. With his translucent washes of vibrating, thinly-applied colour, offset by darker, denser patches, Girtin established water-colour techniques which are still in use today, notably in a good deal of Tillyer's work.

This sense of precocious modernity is intensified in the early work of John Sell Cotman, who painted in large areas of flat washes and clearly-defined planes, orchestrated into strongly decorative patterns. It is hard for us to look at these works without thinking that they anticipate Cezanne. There is something almost shocking about Cotman's resort, later in life, to thick and gaudy rice impasto, for it seems that in the rhythmic washes of his early works there is a complete union between the desired effects and the means used to achieve them.

This, I think, is what Ruskin was getting at when he wrote that Girtin's work was often as impressive to him as Nature itself. I feel Ruskin was right when he claimed that water-colour looks much more lovely when it has been laid on with a dash of the brush and left to dry in its own way, than when it has been dragged about and disturbed. He argued that it was 'always better to let the edges and forms be a little wrong, even if one cannot correct them afterwards, than to lose this fresh quality of the tint'. As a lesser critic put it, writing in the Edinburgh Review of 1834:

The dewy freshness of a spring morning - the passing shower, - the half-dispelled mist - the gay partial gleam of April sunshine - the rainbow - the threatening storm - the smiles and frowns of our changeful sky, or their infinite effects upon the character of the landscape - the unsubstantial brightness of the grey horizon - and the fresh vivid colouring of the broken foreground - all these features in the ever-varying face of Nature can be represented by the painter in water-colours, with ... a day-like brightness and truth, which we will not say cannot be produced in oil-painting, but which we at least have never yet witnessed . . . All that we have yet seen inclines us to think, that, in the representation of land, sea, and sky, the art of water-colour painting which has so recently begun to be cultivated, and is probably so little advanced towards the possible perfection, is superior to the long- established art of painting in oil.

Northumberland, sky and woodland.

These judgements point towards an intriguing conclusion which neither Ruskin nor the anonymous critic of the Edinburgh Review was able to draw: namely that in water-colours, and perhaps only in water-colours, the great cry of the Romantic aesthetics, ('Truth to Nature') and that of emergent Modernism ('Truth to Materials') were, in effect, one and the same. When used in a way which preserved the particular qualities of the medium (even at the price of losing immediate resemblance to the appearances of things), water-colour painting seemed to come closest to embodying the fragility and spontaneity of our perceptions of nature itself. I think it is this unique property of the medium that Tillyer has understood so fully.

During the nineteenth century, a great split began to appear in aesthetic life, a split between those who believed in the pursuit of 'Natural Form', as the means to spiritual truth, and those who, in the phrase later made popular by Roger Fry and Clive Bell, set out in quest of abstract 'Significant Form'. Walter Pater was perhaps the first critic to elaborate a critical response which radically rejected mimesis - or imitation of appearances - as a means to truth. Pater argued 'art comes to you professing frankly to give nothing but the highest quality to your moments as they pass, and simply for those moments' sake'.

Whistler took these ideas and wittily vulgarised them in a thoroughly American way. 'Art,' he declared, 'should be independent of all clap-trap, should stand alone, and appeal to the artistic sense of eye or ear, without confounding this with emotions entirely foreign to it.' He went on to explain that he insisted on calling his own works 'arrangements' or 'harmonies' - whatever their depicted subject matter.

It was in America that such aesthetic ideas were to be pushed to their ultimate conclusions, most nobably in the writings of Clement Greenberg. These days Greenberg insists that his critical counsels have always been descriptive, not prescriptive, but in 1944 he wrote, 'Let painting confine itself to the disposition pure and simple of color and line, and not intrigue us by associations with things we can experience more authentically elsewhere.'

The painter, he said, 'may go on playing with illusions, but only for the sake of satire'. Greenberg believed the best art was launched on an 'ineluctable' quest for its own essence. Avant- garde painting and sculpture, he maintained, had attained a thorough-going purity. They were in the process of becoming 'nothing but what they do; like functional architecture and the machine, they look what they do. The picture . . . exhausts itself in the visual sensations it produces.'

Towards the English lakes.

Greenberg's aesthetic corresponded with Post-Painterly Abstraction, as practised by Morris Louis, where thin films of paint applied to the canvas surface produce vibrant, if slight, aesthetic sensations.

In England such goals were never pursued with the reductionist urgency of the Americans. The intellectual heritage of empiricism and perhaps even our native geography and weather, combined to encourage the belief that aesthetic values could be rooted in some sort of imaginative experience of the natural world. There were many different ways of doing this, and the old Romanticism persisted in increasingly exhausted guises. I'm thinking of the pastoral tradition which passes through John Linnell into the 'Romany' paintings of Augustus John, to Alfred Munnings and Russell Flint.

Far more radical was that 'Neo-Romanticism' of which I have written so much elsewhere. Graham Sutherland, Henry Moore, and John Piper were among those who tried to confront an injured nature as a wasteland from which God had departed. They struggled to depict landscape in a plastic, rather than a scenic way. Predictably, Greenberg made Neo-Romanticism a polemical target. But there was also a third route: that which tried to explore landscape in a way which remained compatible with the peculiar quests of Modernity for an art of sensations, 'truth to materials', and restless questioning of the conventions of illusion.

This was more successful than has often been admitted, and, predictably, water-colour has played a very important and still underestimated part in the development of this tradition. I am thinking, especially, of those magnificent paintings which Wilson Steer produced on his painting trips in the 1920s and 1930s - works like A Calm of Quiet Colour, Totland Bay, 1931, or Showery Weather, Mill Beach, 1933. Here we find that fusion of truth to nature, and to materials and techniques, which lies in direct continuity with the achievement of Girtin.

It was such a quest which animated Ivon Hitchens and so many of the St Ives painters in the immediate post-second world war period. Some, most notably Peter Lanyon, were clear about what they were doing. Lanyon always resisted the idea that he was painting absolute abstractions; and I have always suspected that, notwithstanding his critical views, Patrick Heron's sensibility, too, owed a great deal to his response to nature. Others, however, were seduced into the American belief that thoroughly Modern work must dispose of any Romantic residues, that is, of any resemblances, however slight, to natural form. This may account for all the confusions and contradictions that swept through the St Ives aesthetic in the late 1950s, and early 1960s - all the hostility to horizon lines, to 'natural' colours, to any trace of Neo-Romanticism, or a quest for spiritual values. Indeed, the next generation of London- based 'Situation' painters conducted a puritanical purge of any such features, reducing their work to an anaemic reflection of the American Late Modernist aesthetic.

William Tillyer, who was born in 1938 and studied at the Slade in the early 1960s, was of this generation. He is, I think, as questioning as any of his contemporaries about the nature of plastic form, and painting itself. And yet he did not believe that the argument had been definitively 'resolved' in favour of the formal and physical dimensions of picture-making. Tillyer seems to me to have gone back to the point where Lanyon and Heron left the argument. Despite his firm grasp of Modernity, he was to revive even older ways of working and replenishing his work.

In 1981, Tillyer took up a post in Australia as artist-in- residence at Melbourne University. We cannot be sure why, but the vastness of Australia's inhospitable terrain always challenges and unsettles a sensitive European's response to nature. In 1982, Tillyer held a major exhibition at the university gallery. Soon after that, while working on his 'Yorkshire Bridge' paintings, he decided that he wanted to establish the Romantic, illusionistic, and indeed, spiritual dimensions of his painting more unequivocally, without sacrificing his self-conscious concern with the physical and the formal. To this end, Tillyer turned to water-colour, becoming as diligent as Wilson Steer in seeking out new locations. He moved restlessly from one painting venue to another in France, Italy, Switzerland, America and, most recently, the north-east of England. Far from seeking to purge his painting of intimations of nature, Tillyer seems to want to find a new (and Modern) vision of the natural world. I believe this is why his art is attaining a new beauty and subtlety at a time when so many of the 'Situation' generation have entered a fatal cul-de-sac. I hope that enough has been said about the nature of watercolour to indicate at least part of the reason why it was appropriate to Tillyer's aesthetic needs. With his best watercolours we find ourselves delighted by works which declare their Modernity, originality, plasticity and topographical scepticism, while simultaneously affirming that they are part and parcel of a particular English tradition which may be traced back as far as Dr Thomas Monro's workshop.

Not surprisingly, Tillyer has tended to agitate 'informed' critics who react to what they perceive as his fidelity to anachronistic practices and techniques. Today the artist is not expected to pack up his water-colours, pick up his painting stool, and journey to inaccessible places - in short, to behave like Edward Lear. Even if he does, he ought to have the good grace to return with readily identifiable, topographic studies, so that we can all see just where he has been and how quaint and old-fashioned his outlook is.

And yet slowly the tables may be turning. For Greenberg, one of the virtues of thoroughly Modern art was that it refused any appeal to spiritual values, resting upon sensation alone. But Fry could never have been content with such a position. His only interest in 'Significant Form' was as a vehicle, or avenue, to the realm of the spirit. 'Art,' he wrote, just before he died, 'is one of the essential modes of our spiritual life.' Whatever American critics have taught and American artists have done, a large part of the British public have held fast to Fry's belief. Today, the severance which Late Modern art seemed to demand from the realms of illusion, spirit and nature is beginning to be seen as its greatest weakness. An abstract 'art of the real', which excludes such concerns, leads to inevitable aesthetic failure. The search for spiritual values in some kind of imaginative, if secular, response to nature is becoming almost respectable again.

The great strength of Tillyer's water-colours is that although they are unequivocally Modern, they are the kind of 'pure' works of art which, as Fry put it in his Last Lectures, 'set up vibrations in the deeper layers of our consciousness and . . . these vibrations radiate in many directions, lighting up a vast system of correlated feelings and ideas'. Tillyer's water-colours invite us to share with him a tentative and tremulous sensation of physical and spiritual oneness with the natural world.

North Yorkshire, a barn, Murk Mire.

These are not experiences of a kind which photographs or annotated Ordnance Survey Maps could ever provide. Richard Mabey, one of the most perceptive writers on rural themes, has bitterly criticised 'that glib blurring of meanings, that appropriation not just of the whole countryside but the whole nation to a single point of view about our proper relationship with nature', so characteristic of the contemporary world. By contrast, he stresses the 'immense range of experiences of natural life and landscape reaching back through our history and often beyond any narrow definition of rural traditions', which, he insists, 'is part of a common culture'.

I believe that Tillyer's enticingly beautiful water-colours reunite us with that 'common culture' in a way which does not compromise our Modernity. Beautiful in themselves, true at once to nature and to materials, Tillyer's gentle washes of colour have a wider meaning. They remind us that if we divorce our highest aesthetic emotions and perceptions from the world of nature, we will be more inclined to injure and to exploit the natural world - and indeed, each other - than if we perceive ourselves as being part of it.

Peter Fuller 1987

The latests exhibition of Tillyer's work is on view at the new Bernard Jacobson Gallery venue in Duke Street from 1st-30th May 2015.