MODERN ART intertwines a life-long battle between four mavericks of the art world, escalating to a crescendo that reveals the purpose of beauty, and the preciousness of life. Based on the writings of Peter Fuller, adapted by his son.

A NEW SPIRIT IN PAINTING?

by Peter Fuller, 1981

Installation of A New Spirit in Painting at the Royal Academy, 1981.

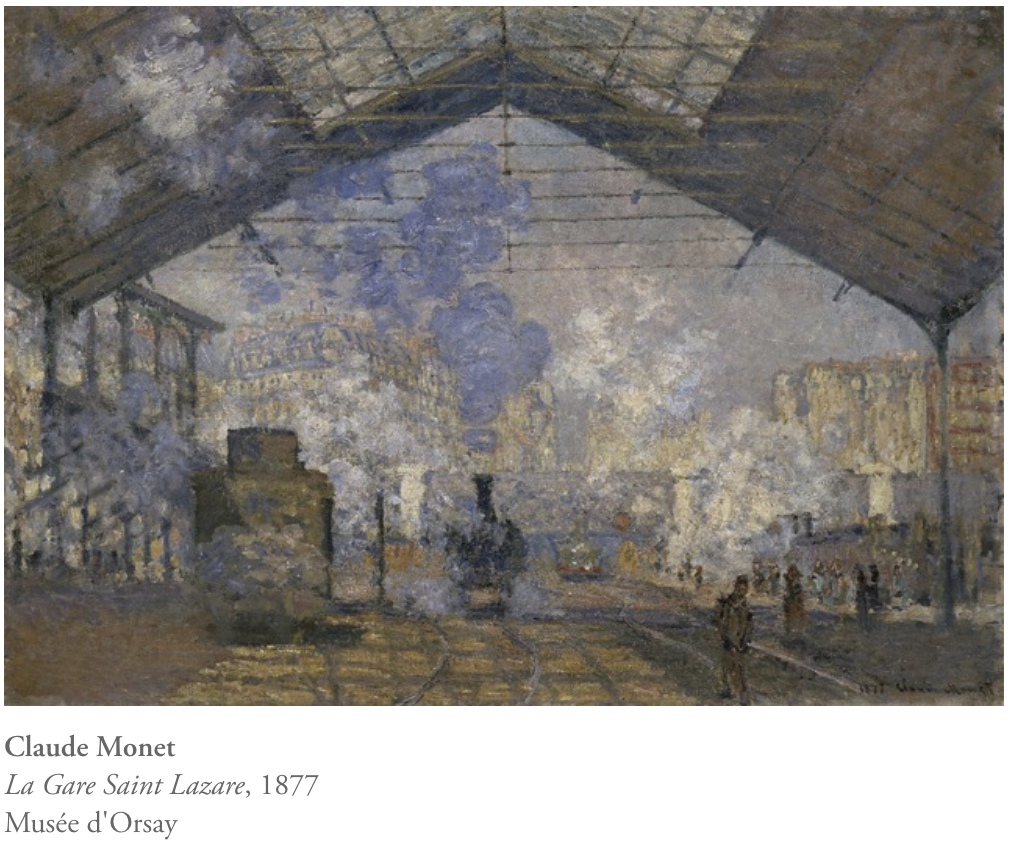

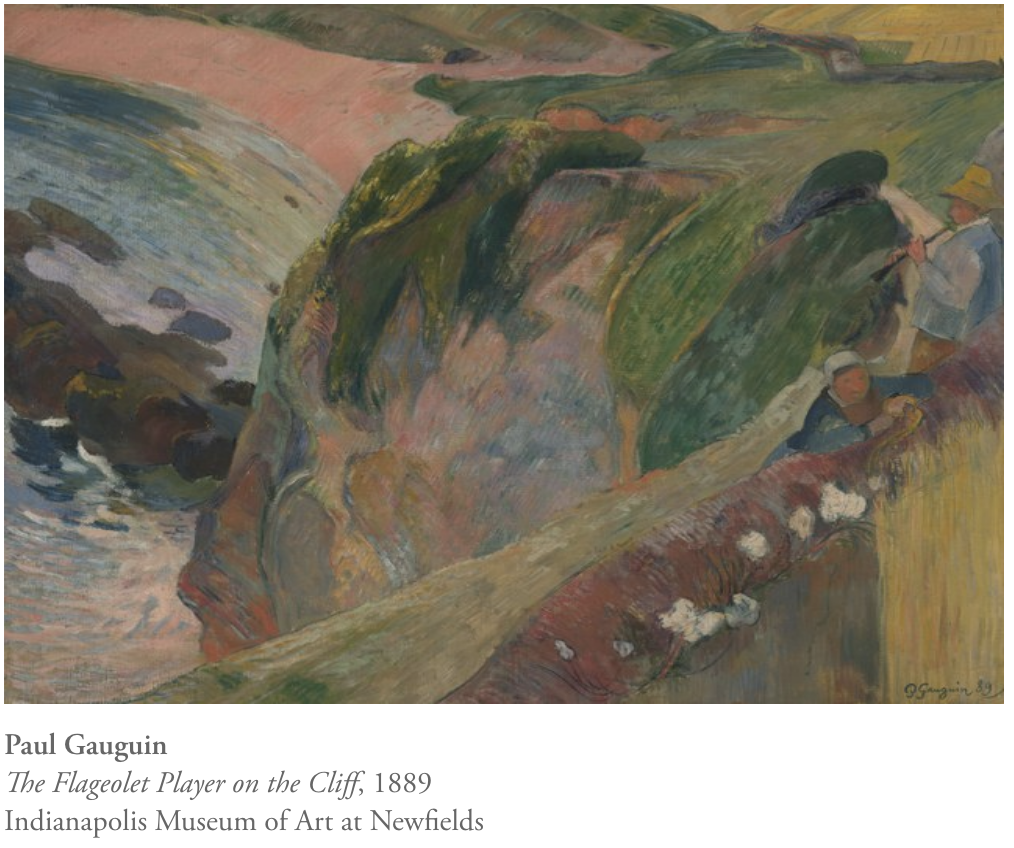

Over at Burlington House, home of the Royal Academy, the trumpets sounded and A New Spirit in Painting was proclaimed. Hugh Casson, President of the Royal Academy, wrote that the massive exhibition of 145 large pictures was ‘a clear and cogent statement about the state of painting today.’ He even compared the show with Roger Fry’s famous Post-Impressionism exhibition at the Grafton Galleries, seventy years ago, when Cezanne, Van Gogh and Gauguin were introduced to a sceptical British public.

Three organizers chose the recent work of thirty-eight artists from Britain, Europe and North America. The exhibition ranged freely across the generations: there are very late works by Picasso; by Matta, the Chilean surrealist; and five recent paintings by De Kooning, the last survivor of the ‘classical’ generation of American abstract expressionists. But there were also works by Germans and Italians in their thirties and forties which have been but little seen outside their home countries. Everything in the exhibition, however, was painted during the last ten years. It was a crusading exercise intended to give the lie to recent rumours about the health of painting and to demonstrate that ‘great painting is being produced today.’

In the catalogue, the organizers argued that the existence of such work has been obscured by a ‘one-track’ reading of art history, biased in favour of a succession of recent styles in American art. A catalogue essay brushed aside the view that painting has been rendered obsolete by photography, and affirmed the enduring possibilities of the traditional medium. Imagination, individuality and subjectivity were celebrated; the exhibition, we were told, presented a position in art which conspicuously asserted traditional values—such as individual creativity, accountability, and quality; but ‘for all its apparent conservatism the art on show there was, in the true sense, progressive.’

At the level of rhetoric, this is splendid stuff. Indeed, for some time now, I have been arguing much the same against the orthodoxies of the institutionalized, salon ‘avant garde,’ and the social reductionists of the left alike. The more that I was exposed to the thin diet of reductionist modernism, the more I came to realize that my views about painting were radically conservative, though not, I hope, reactionary.

The Head of JYM, Frank Auerbach

So perhaps it was not surprising that I found some things in the exhibition to admire. For example, I have long thought that Frank Auerbach was among the best living British painters. Fie combines a close, empirical observation of the external world with a vividly imaginative expressionism: the two elements are brought into unity in his successful paintings because he is a master not only of drawing, but also of that lusciously thick impasto with which he paints. The Head of JYM characteristically combines the fathering-forth of the beauty of past change with an accuracy of observation, and a taut economy of scale which most of the other exhibited artists would have benefited by studying.

Similarly, although I think that a lot of Ron Kitaj’s painting falls short, I am equally certain that his If not, not is among the few really good pictures produced in Britain during the last decade. The painting is frankly utopian: it is like a dream of a world transformed. I was moved by this picture when I first saw it in 1976, and I have lived with a reproduction of it for some time. As in all good painting, form and content are virtually indistinguishable.

The picture is effective because Kitaj has managed to bring his extraordinarily inventive powers as a draughtsman and colourist into a convincingly unified composition, through which he is able to realize that ‘other world’ (the ‘subject’ of his painting) on canvas. It may, however, be indicative of the faulty taste of the organizers of this exhibition that If not, not, though entered in the catalogue, was withdrawn from the show sometime between the press view and the opening of the exhibition to the public, although a great deal of unconscionable rubbish was left hanging there.

Young Bather with Sand Shovel, Pablo Picasso

There were some other works which I found interesting. Like John Berger, I once believed that Picasso’s best pictures belonged to his cubist phase, and that what came later was essentially a falling off. Picasso, Berger argued so convincingly, became the prisoner of his own virtuosity—an artiste in search of a subject. But the four paintings shown—all produced within two years of his death in 1972—impressed me deeply. Young Bather with Sand Shovel, for example, was more expressive, and pictorially impressive, than many of Picasso’s cubist works. I also respected Lucien Freud’s portraits of his mother, which rely upon the expressiveness of carefully perceived physiognomy; and the sensuousness, complexity, and compactness of Howard Hodgkin’s abstractions. Hockney’s new paintings, though better than most exhibited here, are much less achieved than either his earlier pictures, or the beautiful drawings which he exhibited recently at the TATE.

But could such things be said to amount to ‘a new spirit in painting’? Well, hardly. Few of the good works in this exhibition are informed by freshly conjured genie. Recent art history has certainly over-estimated the importance of stylistic innovation; but it did not thereby obscure from view much worth seeing that is on show here.

After all, Hockney cannot be said to have been hiding his lights beneath a bushel; nor did Picasso’s talents pass unnoticed during his lifetime. If the spirit of painting lives on in this exhibition it cannot be said to have been born anew. On the other hand, a great deal of the work here is not just bad: it is also in no way compatible with the verbal rhetoric of the catalogue, which emphasizes the specific physical processes involved in painting and the possibilities for imaginative expression to which these give rise.

Take the work of Andy Warhol. Instead of using his eyes to look at reality, and his imagination to transform what he saw, Warhol simply picked up ready-made images (like can labels, dollar bills, glamour photographs, and so on) from commercial art. He turned these into ‘paintings’ by the use of mechanical reproductive means, like silk-screening and photo-based techniques. Some paint was occasionally added, usually by Warhol’s assistants. He thus not only debased the significance of the artist’s particular vision (in both senses of that word), but ensured that there could be no relationship between his imagination, and the concrete working of his forms in paint.

Since a Warhol painting owes so little to his imagination, touch, draughtsmanship, colour or compositional skills, any residue of aesthetic effect to which it gives rise can only be fortuitous: a matter of chance, or the ideological assumptions of the viewer. Warhol is thus the antithesis of a fine painter like Auerbach, who conserves and employs all those expressive potentialities peculiar to painting which Warhol jettisoned. Warhol’s work, for me, is style unredeemed by an iota of expressivity; he is fundamentally inauthentic. Indeed, he epitomizes what has gone wrong with painting in the last twenty-five years; one might have expected the heralds of any ‘new spirit’ to begin by rejecting him.

But instead, the Academy show includes some even more reductionist work, by the American, Brice Marden, who juxtaposes dead rectangles of flat colour; and Alan Charlton, an over-exposed British painter whose unsubtle grey monochromes have long symbolized for me the wall at the end of the late modernist cul-de-sac. In Charlton’s work even the vestiges of the painter’s imaginative and material powers have been relinquished: he is an artist who has nothing to say, and no way of saying it either.

Partisan, Georg Baselitz

At first sight, much of the work by younger European painters—in particular by certain Germans—seems rather different. Pictures by Baselitz and Liipertz, for example, look as if they want to be thought of as being ‘expressionist.’ But as soon as you attend to them, you realize they are every bit as mannerist as Charlton’s or Marden’s. Their scale has been inflated out of all proportion to their content as if to say to the Americans, ‘Look! We can do it bigger still!’ But there is more excuse for oceanic size in a work whose effects depend upon colour rather than drawing; the drawing of these Germans, however, gives them away.

Just compare their loose and vapid lines with the sort of truly expressive handling you find in, say, Auerbach. The difference is that Baselitz and Liipertz are just ‘expressionistic’ —i.e. the look of their paintings is derived from copying the style of European expressionism. There is little in their paintings which they have seen, felt or created for themselves. That is why they have to resort to all sorts of desperate devices—like hanging pictures the size of cricket pitches upside down, or repeating the same image over and over again—in order to try and attract attention. But they end up in a mire of murky rhetoric, producing wall-paper versions of the German art of half a century ago.

The elevation of these varieties of empty rubbish at the Royal Academy is as predictable as it is saddening. But The Story of Modern Art notwithstanding, quality in art is not a question of style, ‘expressionistic’ or otherwise. It remains a matter of debate as to whether truly great painting can be produced in a society in which mechanical means of reproducing images are ubiquitous; traditional crafts have decayed utterly; and the shared symbolic order characteristic of a dominant religion has collapsed. But good painting certainly remains possible: it has much to do with a certain quality of imagination and the development to the point of mastery of the material skills specific to the practice of this art. Those skills include drawing (which can only be learned in the first instance from the figure and the object) and colour—which must be sought in nature.

Expression in painting, thus understood, is not reducible to historical circumstances but is rather a material process, incorporating certain significant biological elements which draw their strength from ‘relatively constant’ aspects of human experience. Late Modernism’s reductive pursuit of next season’s style, or the contents of the next room in the Museum of Modern Art, involved the relinquishment of all the constituent elements of painterly expression. This exhibition does not reject this trajectory: rather, it tries to associate a ‘new spirit’ in painting with this old vandalism, and some of its most sterile products. Worse still, it repeatedly mistakes expressionistic mannerism for true expression. But, after all, what else is one to expect from an academy . . . ?

1981