A new Julian Schnabel show is on at the Legion Of Honor in San Francisco until August 5th 2018, to mark the finishing touches that have just been made on the working draft of Modern Art, The Peter Fuller Project, I wanted to play contrarian by posting Peter's article on Schnabel. He always had very strong opinions about his work, and despite their several encounters was never able to shift his view. I've always loved Schnabel as a filmmaker ever since I saw Basquiat when I was a boy, since I've equaly loved Before Night Fall and Diving Bell & The Butterfly. Schnabel says he considers himself more the painter than the filmmaker, but I can't help but wonder what his take on Modern Art might be.

Julian Schnabel

By Peter Fuller

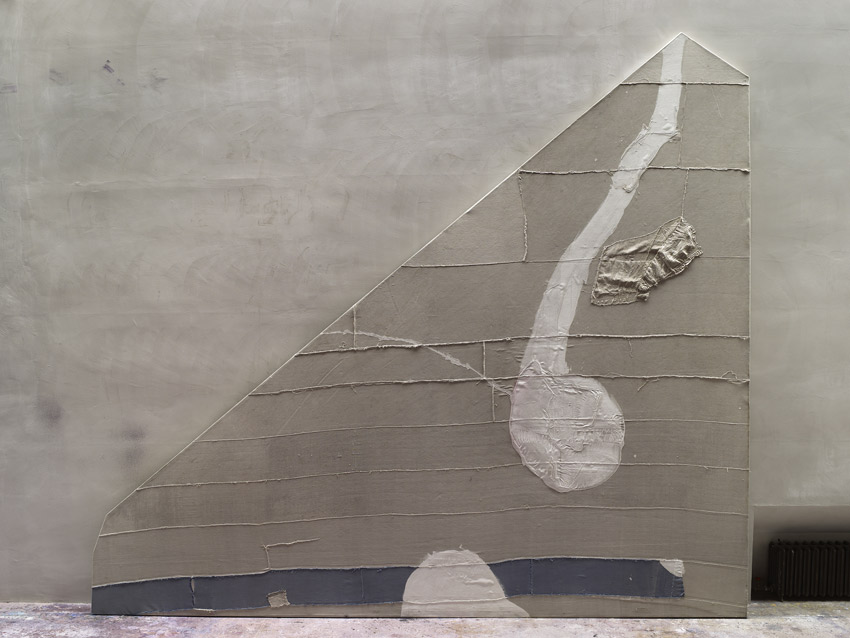

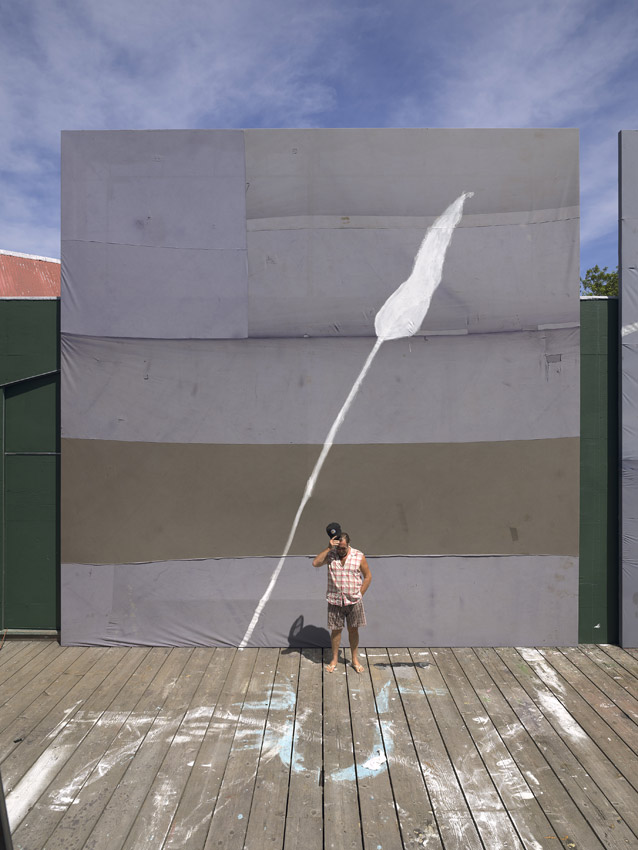

Over the last four years I have seen a good many of Schnabel’s paintings, but I had not, until this exhibition, set eyes on one that manifested any painterly qualities at all. I was therefore pleasantly surprised to look at a picture like Alexander Pope, which indicates that Schnabel could conceivably learn to draw; or at Seed, which shows that, after all, he might have some decorative sensibility. Drawing and decorative sensibility are, you must understand, two of the necessary prerequisites for good painting.

But I don’t want to exaggerate Schnabel’s slender talents. At the private view, I stood beside Kasmin and Gillian Ayres (yes, we were all there) in front of Alexander Pope, and Kasmin confided that if he had seen the painting in a studio in Wapping he wouldn’t have given it a second thought. Nor should he have. The average first-year intake in any British art school includes several painters capable of realising better work than Schnabel at his best.

At least I hope it does. For whatever flickerings of potential this young tyro possesses, they cannot cover up the fact that he is a painter with the imagination of a retarded adolescent; no technical mastery; no intuitive feeling for pictorial space; no sensitivity towards, or grasp of, tradition; and a colour sense rather less developed than that of Congo, the chimpanzee who was taught (among other things) a crude responsiveness to colour harmonies by Desmond Morris in the late 1950s. However potentially educable as a painter Schnabel may or may not be, his work is just not worthy of serious attention by anyone with a developed taste in this particular art form.

And yet, sadly, this cannot be the end of the matter. We also have to contend with the fact that, as Richard Francis so accurately put it in his hagiographic Tate catalogue, ‘Julian Schnabel, born in 1951, has become, since his first exhibition at Mary Boone’s gallery in New York in 1979, one of the most celebrated young artists working anywhere in the world today.’ How can this be?

More than once, the comparison has been made with Jasper Johns, who was an overnight success following his first one-man show with Leo Castelli (a business associate of Boone’s) in 1958. Johns appeared on the cover of Artnews - until that point a tendentious ‘abstract’ journal, MOMA immediately bought work and the show was a sell-out even before it opened. ‘Abstract Expressionism is Dead! Long live Pop Art!’ they cried. And Castelli totted up the takings from his cultural coup.

There are similarities, of course; but the comparison is unfair to Johns. He may not have been Leonardo, but he did have some realised talent. He could, and still can, draw quite well. He worked terribly hard at getting his intractable surfaces right. He could even think a bit too - even if not as much as his fruity protagonists and fruitier prices suggest. If Johns was hyped, it was on the basis of some remote kernel of achievement. But Schnabel?

The qualitative distinction is important because it is often implied that market activity, on its own, provides a complete ‘explanation’ of why an artist of such low quality as Schnabel has achieved such cultural prominence. The thesis underlying this view is that good art and entrepreneurial economic activity are somehow necessarily antithetical, whereas cultural prominence and market success are necessarily linked: though fashionable and congenial, I believe this theory to be nonsense.

If you disagree with me, you clearly have not got round to visiting ‘The Genius of Venice’ at the Royal Academy: this you really should do since it is undoubtedly the finest art exhibition to have been staged in the capital in living memory. Sixteenth- century Venetian painting was flushed with the residues of religious illusions; but it was, par excellence, an art created for a new breed of princely merchants. In form and in content, the freestanding oil pictures of the day reflect this emergent secular mercantilism; they are enthused by the values of the Rialto rather than St Mark’s.

Sixteenth-century Venetian art celebrated mercantile materialism in its subject matter; it manifested a relish in exotic fabrics, fine furs and silks, precious metals and stones, and ample acreages of enticing female flesh. It also showed a parallel sensuality in the medium itself: the sensuous possibilities of oil were excitedly discovered and exploited. Now, of course, we may or may not like the ethical values and economic systems which provided the social soil for these sumptuous pictures: but we could deny neither that they were closely related to intense market activity, nor that sixteenth-century Venetian painting is one of the very greatest of all human achievements in the plastic arts.

Nor is this association between a market economy and the efflorescence of creative activity an isolated instance. There is, for example, the lesser, but none the less considerable, case of the achievement of seventeenth-century Dutch painters, which evolved in conjunction with the expansion of a domestic picture market. The vision of these painters was petty bourgeois in content, subject matter, and form. (How neatly their pictures fitted into the trim interiors they depicted.) And yet who would deny that, say, Vermeer was one of the finest painters to have emerged in the West?

Even in more recent times, there is no necessary connection between the determinative influence of an active market, and degradation of aesthetic quality: the worst that can be said of the market in our time is that it is fragmented, but all its differing sectors taken together are effectively aesthetically neutral, since they elevate good and bad alike. Thus whereas it is perfectly true the market can sell anything - even folded blankets, canned shit, twigs, bricks and so forth - there is no evidence that such phenomena were caused by the market, nor that the market prefers such things, nor even that it welcomed their arrival. Indeed, it could credibly be argued that much of the most decadent art of our time only came into view because those who produced it were insulated from the full impact of market forces, either through the possession of private wealth, or, more recently, through the existing system of ‘hands-off’ government patronage.

Dealers do not have to be altruistic to prefer works of quality to fashionable rubbish; not only is good art an easier sell, it is also a much better long-term investment prospect. But there is, of course, no direct channel between market success and cultural prominence. If you study the art market in Britain over the last quarter-century, you will quickly discover that there has been an active market in high-priced, high-quality English painting — for example in the work of Freud, Auerbach or Kossoff. But, until four or five years ago, despite their buoyancy within the marketplace, these painters received virtually no art world attention: their bibliographies are still very much shorter than Schnabel’s today. There has also been a very active market in high-priced works of low or negligible quality (e.g. Terence Cuneo, David Shepherd, Montagu Dawson) which still have received little or no critical attention. I conclude nothing from all this, except that intensification of market activity is neither an indication of the presence of aesthetic quality, nor yet of its absence; nor does market success lead in any simple or necessary way to the sort of cultural over-exposure which young Schnabel is currently enjoying.

So we have to look deeper. We have to ask what sort of market, and who is it serving? What sort of cultural values do the patrons of this kind of art hold? The point is not that the Saatchis are rich: it is rather that, despite their wealth, they do not have the taste of those merchant princes, honest innkeepers of seventeenth-century Holland, or even the wealthy country-house aristocrats who have been buying Lucian Freuds all these years.

The Saatchis spend their working lives promoting a dominant cultural form, advertising, which allows no space for the social expression of individual subjectivity. It is therefore predictable that, unlike merchant princes, aristocrats, Dutch innkeepers and others who possessed both wealth and taste, they prefer fine art forms which are nothing but a solipsistic, infantile wallowing in the excremental gold of the otherwise excluded subjective dimension. Schnabel and Waddington are entitled, if they so wish, to serve the tasteless sensibilities of the advertising tycoons. But it is one thing for such people to pursue their degraded tastes in private, and quite another for our leading modern art institution, the Tate Gallery, to indulge those tastes in public. I believe that Alan Bowness should indicate to us what the true aesthetic qualities of the Schnabels he has so freely purchased are: and if he cannot do so, he should resign.

1984