In honor of David Hockney's 80th birthday I wanted to share this article All The World's A Stage by my father Peter Fuller, it's one of the last pieces he wrote on Hockney, though they were lifelong friends and he wrote about Hockney's work since the late Sixties. In true Peter Fuller fashion it starts out talking about Hockney's art direction for various theatre productions and spirals into a retrospective of his life and career and the strangeness of subjectivity which always seemed to permeate their discussions.

ALL THE WORLD'S A STAGE

by Peter Fuller

'Well, I'm not that interested in the theatre itself,' David Hockney said in 1970. 'I did one play. I designed Ubu Roi. When I was doing that, I suddenly realised that a theatrical device in painting is quite different to a theatrical device in theatre.' He added, 'I'm really not interested in theatre design or anything.'

Four years later, John Cox, a producer, invited Hockney to design a new production of Stravinsky's opera, The Rake's Progress, for Glyndebourne. Predictably, Hockney had profound misgivings, but he loved opera and he was experiencing a deep crisis of confidence about his own painting. The idea of working in a new medium appealed to him. So, too, did the subject matter. Hockney himself had made a 'modern life' version of Hogarth's famous series of prints in the early 1960s. He accepted Cox's offer, and the resulting designs were shown in the exhibition, Hockney Paints the Stage, at the Hayward Gallery in August 1985.

Hockney insisted that the opera should be set in the eighteenth century - as reinterpreted from a twentieth-century viewpoint. Even though the relationship between Igor Stravinsky's work and Hogarth's is tenuous, Hockney decided to make persistent reference not just to the subject matter but also to the pictorial techniques of Hogarth's prints. He made use of dramatic perspectival foreshortenings - especially in the Bedlam scene; and, improbably, turned even cross-hatching into a theatrical device. Intersecting lines covered not only the back-drops, but even the furniture and the costumes, creating the illusion that everything has been 'engraved' in three dimensions. The result proved so original and effective that Hockney was immediately invited to design a Magic Flute which was staged at Glyndebourne in 1978.

During the year he spent working on Mozart's opera, Hockney produced no paintings at all. Again, his sumptuous sets captured the audiences' imagination. In 1981, he went on to complete two triple bills for New York's Metropolitan Opera House. The first of these included Satie's Parade, Poulenc's Les Mamelles de Tiresias, and Ravel's L'Enfant et les Sortileges; the second, three works by Stravinsky.

Soon after, Martin Friedman, director of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, invited Hockney to make the exhibition, Hockney Paints the Stage. Friedman was concerned about the best way of displaying the sets in an art gallery. Sarastro's marvellous utopian kingdom in The Magic Flute, peopled with strangely costumed beasts, was one thing on an opera house stage, but it might be killed stone dead if it was presented simply as a stuffed menagerie against a static back-drop.

For a long time, Hockney appeared indifferent to these difficulties. He was deeply, even obsessively, immersed in his experiments with photography. He argued that the conventional photograph lacked time and therefore life. To overcome this, he started collaging together whole series of exposures and re-integrating them into single images which, he insisted, evaded the fatal photographic flaw.

At the eleventh hour, he managed to tear himself away from his Polaroids and decided to re-create seven stage sets especially for the Minneapolis exhibition. Working at extraordinary speed, on a gigantic scale, he produced what were, in effect, seven autonomous new works. He not only re-painted the props and back-drops himself, but fabricated his first sculptures to represent various characters from the operas and ballets. His esoteric researches into the photographic image exerted a powerful influence on what he produced. Tamino, the flute player in the Mozart opera, became, in Friedman's words, 'a picaresque abstraction of multi-coloured planes'. Hockney himself explained, 'a walking lizard might have twenty feet, leaving a trail behind him to tell us where he has been'. He added that the lizard could have 'three heads in different positions and, as in the photographs, you believe it's one'.

Despite originally denying any interest in theatre design, Hockney's mastery of the medium was hardly surprising. Even when he worked in only two dimensions his principal means of expression had been the playful manipulation of depictive surface and spatial illusion. Behind all the wit and whimsy lay pressing psychological and aesthetic preoccupations.

As every art student knows, David Hockney was born in Bradford in 1937. At his local College of Art he learned to draw, and to paint after the manner of Sickert. He went to the Royal College of Art in 1959 and felt uncertain about what to do there. At first, he spent a lot of time making two painstaking drawings of a skeleton. From this time on, in times of doubt or confusion, he has often fallen back on the apparent certainties of naturalism.

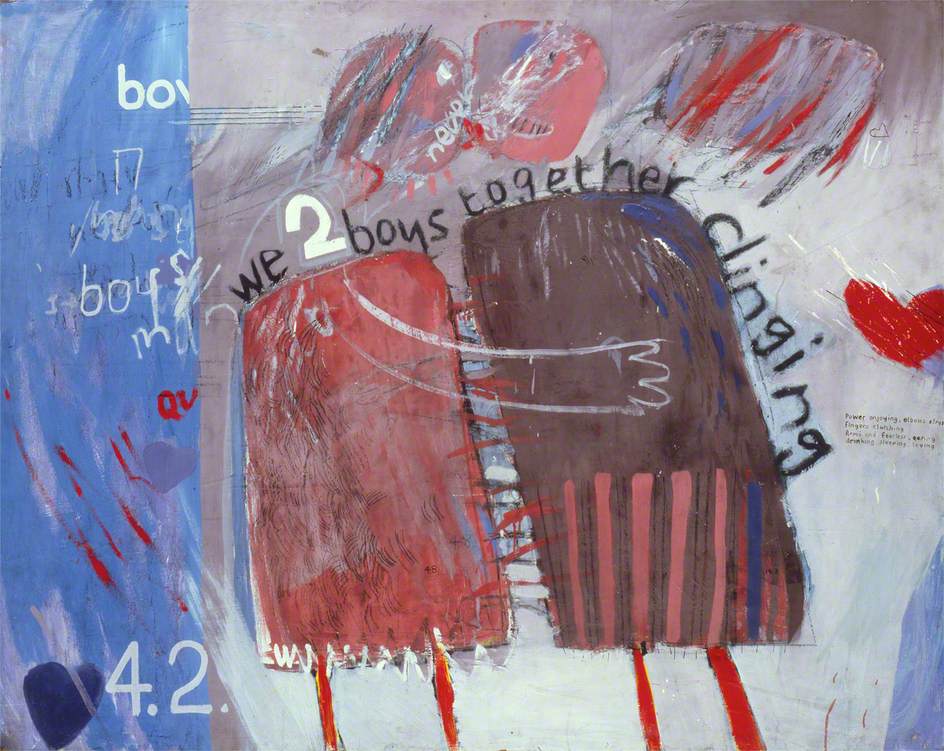

We Two Boys Clinging Together, David Hockney

Those were heady days in the College. Hockney's art soon reflected his espousal of homosexuality, pacifism, Cliff Richard and vegetarianism. His manner of painting now recalled the self-conscious infantilism of Dubuffet, or, closer to home, Roger Hilton. But there was always a sense of deliberate distancing in Hockney. Even at his most 'painterly' - as in We Two Boys Together Clinging - Hockney always held back, like a knowing child, and offered a kind of painted parody of his experience, replete with jokes and ironic references.

Although a gulf divided their sensibilities, Hockney also greatly admired Francis Bacon. Yet where Bacon seemed almost murderously intent upon exposing the post-operative entrails of his subjects, Hockney preferred to dress them up. Many of his early paintings, especially A Grand Procession of Dignitaries in the Semi-Egyptian Style, reveal his interest in the paradoxes of stagey space, performances, tassels and role-playing.

Hockney left the Royal College in 1962 with a gold medal and a ready-made success. He had his first one-man show at Kasmin's the following year. During the 1960s the nature of his concerns became increasingly clear. He showed little interest in the expressive manipulation of his materials, nor did he want to use colour as a means of conveying intense emotion. Although he worked constantly with the male figure, he rarely showed much inclination to reveal character through attention to physiognomy or anatomical gesture. He showed no signs of wanting to involve himself with, say, the way in which natural light fell upon objects, nuanced and revealed them. For a while, at least, artifice was all.

Play Within A Play, David Hockney

At this time he became fascinated by a picture in the National Gallery by Domenichino, Apollo Killing Cyclops, in which the action is depicted through a painting of a tapestry made from a painting. The edge of the tapestry is carefully rendered; in the bottom right-hand corner it is folded back, revealing a 'real' painted dwarf. This picture inspired Hockney's painting, Play Within a Play, which shows his dealer, John Kasmin, with his nose pressed against a real sheet of glass laid across the picture surface. Kasmin stands in a shallow pictorial space behind which hangs the painted version of an illusionistic tapestry.

Soon after making this picture Hockney spent much of his time in California, where he was drawn to the imagery of showers, pools and jets of water. Curtains appear again and again in his work. 'They are always about to hide something or reveal something,' he said. There are also references to the reflective paradoxes the painter encounters when he seeks to represent water. These years, the early 1960s, were a period of high and confident conceit, when Hockney seemed content to remain trapped within a painted world in which illusion opened out onto illusion, revealing no ultimate reality.

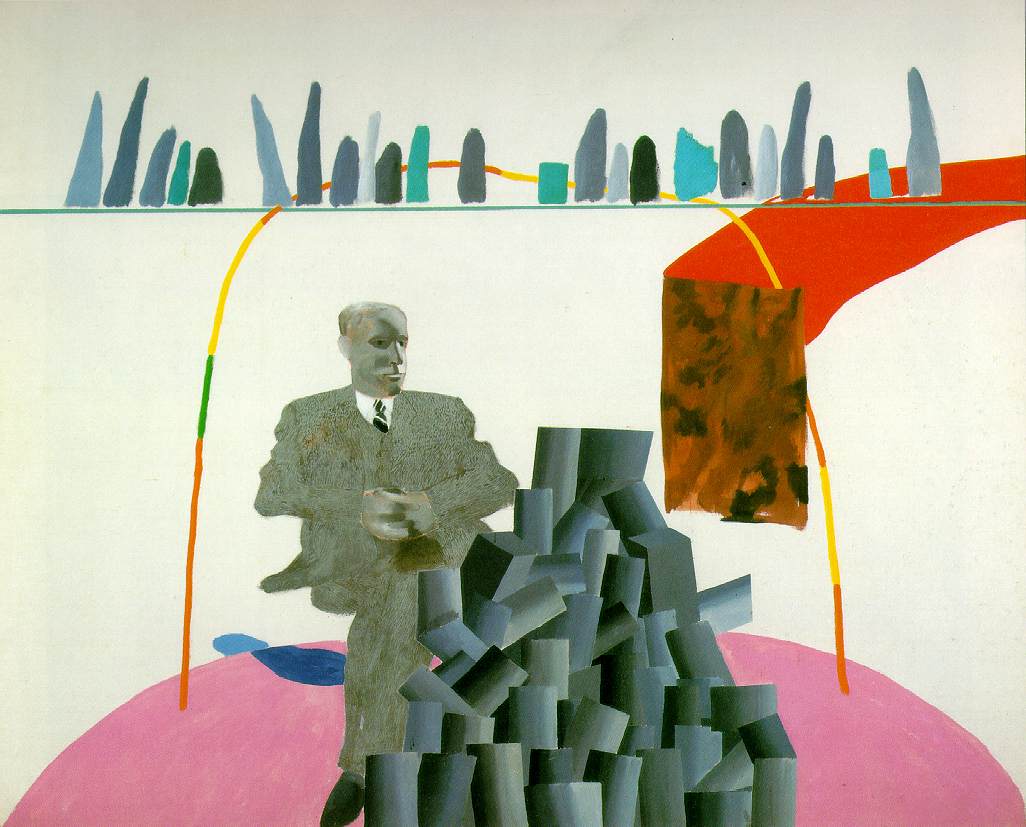

Portrait Surrounded by Artistic Devices, David Hockney

The first hints of change came about in an awkward attempt to do a 'naturalistic' drawing of his father, associated with the painting, Portrait Surrounded by Artistic Devices. Here, a 'realistic' painted father sits beside a stuck-on heap of cubistic cylinders. Two years later, when working on The Room, Tarzana - a portrait of his boy-friend, Peter Schlesinger, laid out like Boucher's pink-bottomed Mademoiselle O'Murphy - Hockney suddenly realised, 'This is the first time I'm taking any notice of shadows and light.'

He then plunged into a series of portraits and set-pieces, including the well-known double portraits of couples failing to relate, which showed a new reliance on the sort of appearances revealed by photography. Indeed, photography was coming to play an increasing part in Hockney's working methods. But this naturalism, too, he soon found cloying. In the early 1970s, he made a number of landscapes, effectively transcribed from photographs which had the dead and unappealing appearance of works by the American Photo-Realist school.

A Bigger Splash, David Hockney

Neither the elaborate devices of Post-Cubism, nor an apparently straightforward naturalism, seemed sufficient to carry Hockney beyond that shimmering pool of narcissistic illusion and self-reflection in which he had imprisoned himself. Following the break-up of his relationship with Schlesinger, Hockney's picture- making entered a period of profound crisis, captured superficially in Jack Hazan's film, A Bigger Splash. He developed a new interest in Van Gogh, whom he regarded as an artist who had been able to deal directly with experience without being either aesthetically innovative or conventionally naturalistic. But Hockney could find no equivalent for Van Gogh's solution in his own painting. Perhaps he came closest to what he was looking for in the fine drawings he made of Celia, his only close woman friend. These possess an intimacy and a sense of otherness, conspicuously absent from so many of his male images.

The invitation to produce the designs for A Rake's Progress came in the middle of this crisis in his picturing. It provided him with an immediate solution: the chance to construct his artifices in real space, to make three-dimensional pictures which had an undeniable existence in a world beyond himself. The culmination of The Rake's Progress work was a painting based on an image by Hogarth, which Hockney called Kerby [see jacket of book]. In this piece, all the devices which should lead to a naturalistic image are reversed or inverted, and yet the picture remains legible.

A Rake's Progress, David Hockney

Hockney tried to combine these discoveries with a replenished naturalism in the portraits of his parents that he produced in the mid-1970s. I remember visiting him at this time in his London studio. He told me, 'When you paint your parents, you paint an idea of them as well. They exist in your mind, even though they are not in front of you. And the problem is, is that part of reality?'

One cannot escape the observation that Mrs Hockney has the face of an ageing Celia, and Celia the look of a young Mrs Hockney. Perhaps he was no nearer an escape from narcissism? In any event, despite going through two versions, the double portrait of his parents was not a success. Hockney abandoned it and subsumed himself in the designs for The Magic Flute.

In the early 1980s he plunged into his critique of the photographic image. Though the 'cameraworks' are not, in themselves, an aesthetic success, they represent another stage in his struggle against being imprisoned within mere illusions of appearances. Once again, Hockney found it easiest to find his 'solutions' by transferring the problem into the third dimension - by making the exuberant, colourful and convincing set-pieces for Hockney Paints the Stage.

With Hockne), the shifting of levels is incessant and compulsive. Many years ago, when he had finished his complex picture of Kasmin trapped behind a sheet of glass, he added irony to irony by having a tapestry made of the image. Then a painter friend visited him and, to Hockney's delight, offered to make a painting from the tapestry.

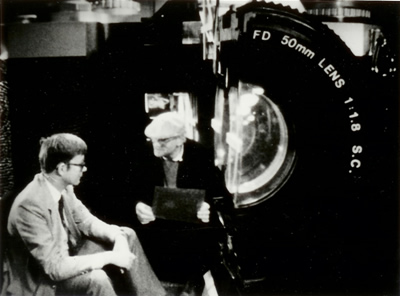

Peter Fuller & David Hockney

At the same time as Hockney Paints the Stage, he also held an exhibition of pictures at Kasmin's Knoedler Gallery in Cork Street, called Wider Perspectives are Needed Now. In this show Hockney re-incorporated lessons he learned from his theatre work into enormous paintings which were like depicted images of those fanciful illusions which he had previously found he cou’d only create in three dimensions on the stage.

There are those for whom all of Hockney's work will amount to no more than a kind of illustrational game-playing. Douglas Cooper was not alone in his view that Hockney was an overrated minor artist. But this is to ignore both his manifest skills and his consistent capacity to entertain. I do not intend this word in any derogatory sense. Most art produced today lacks such a capacity to suspend our disbelief, to hold and engage us. At the very least, Hockney's achievement is comparable to John Fowles's in literature, or Hitchcock's in the cinema. He beguiles his viewers into a world of uncertainty and delightful paradox, but behind the fagade, one senses the most serious intent.

Like his erstwhile hero, Francis Bacon, Hockney sees men and women as somehow trapped within their subjectivity. Perhaps this is where the vicissitudes of the homosexual imagination can appeal to a more general existential condition. For Hockney, as for Bacon, we are like caged animals: the jungle we see is just an illusion, painted on the concrete wall of our enclosure. Bacon's perception of this situation led him to claw his way through the skin into the splayed intestine. Hockney invites us to break through the wall - to confront another illusion, another depicted jungle, on the boundary beyond.

In some ways, Hockney may be a lesser artist than Bacon, and yet I have every sympathy with those who prefer the consolations of Hockney's mirroring artifices, his plays within plays within plays, to Bacon's dubious 'realism'. Bacon can only offer the ultimate presence of death, while Hockney invites us to celebrate the illusion of life.

1985