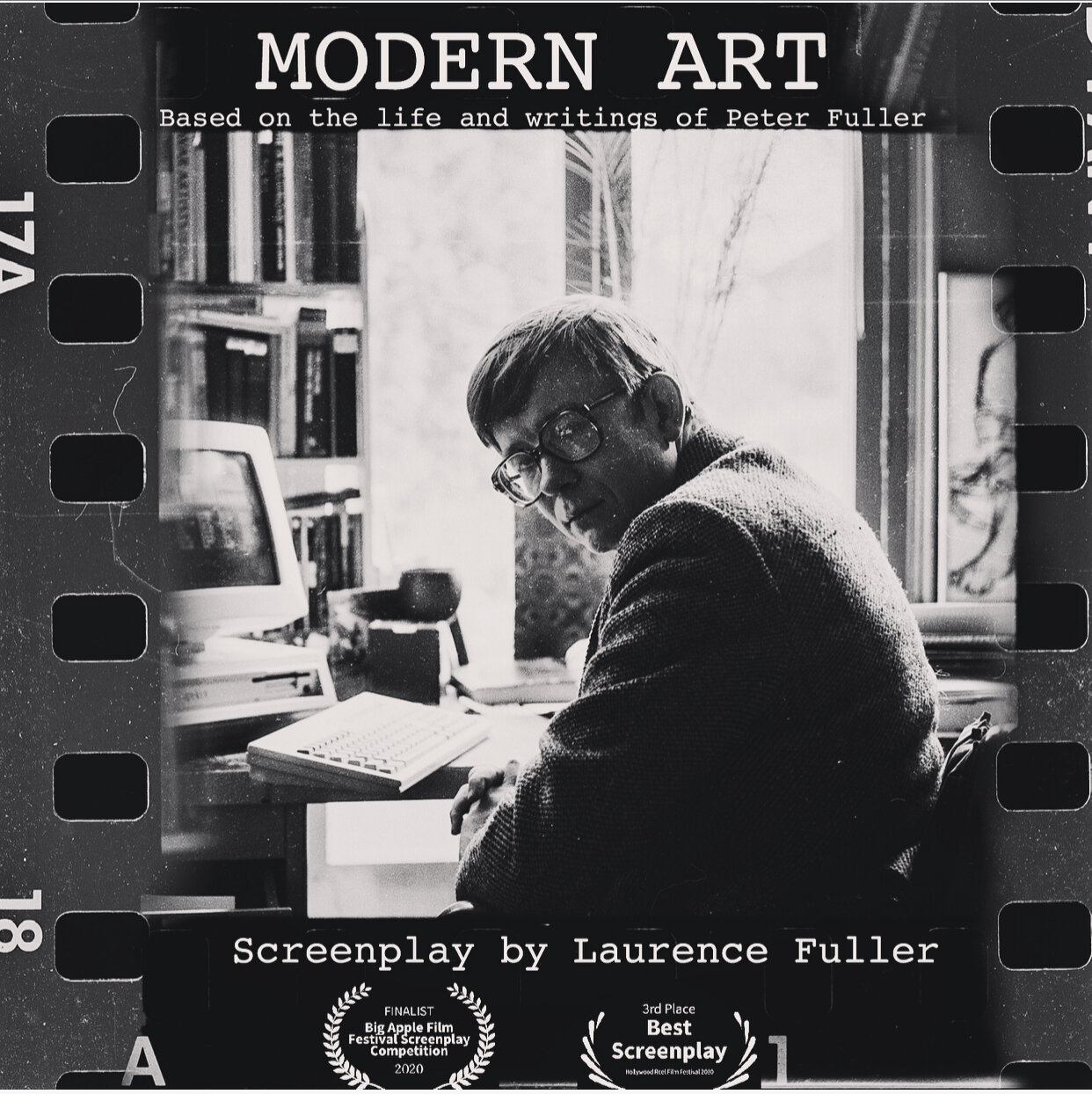

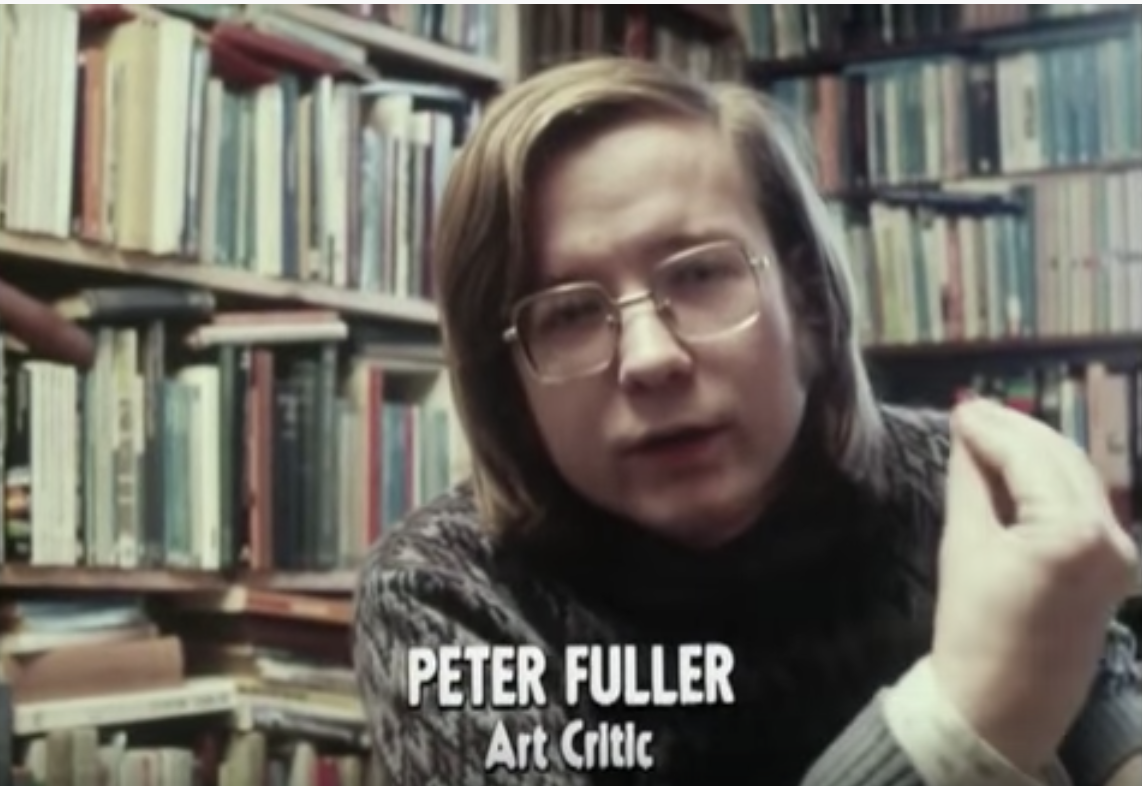

MODERN ART chronicles a life-long rivalry between two mavericks of the London art world instigated by the rebellious art critic Peter Fuller, as he cuts his path from the swinging sixties through the collapse of modern art in Thatcher-era Britain, escalating to a crescendo that reveals the purpose of beauty and the preciousness of life. This Award Winning screenplay was adapted from Peter’s writings by his son.In September 2020 MODERN ART won Best Adapted Screenplay at Burbank International Film Festival - an incredible honor to have Shane Black one of the most successful screenwriters of all time, present me with this award:

As well as Best Screenplay Award at Bristol Independent Film Festival - 1st Place at Page Turner Screenplay Awards: Adaptation and selected to participate in ScreenCraft Drama, Script Summit, and Scriptation Showcase. These new wins add to our list of 25 competition placements so far this year, with the majority being Finalist or higher. See the full list here: MODERN ART

DONALD WINNICOTT

by Peter Fuller, 1980

Laurence Fuller in front of Henry Moore’s “Mother & Child” at The Getty Museum

Donald Winnicott once wrote that he could see what ‘a big part’ has been played in his work ‘by the urge to find and to appreciate the ordinary good mother.’ Before he died in 1971, he had interviewed an estimated 60,000 mothers with their children. His concern was with ‘the mother’s relation to her baby just before birth, and in the first weeks and months after the birth.’ He said that he was trying to draw attention to the immense contribution which the ‘ordinary good mother’ makes to the individual and to society ‘simply through being devoted to her infant.’

Winnicott was among the most innovative and insightful members of that fertile yet contentious school of psychoanalysis which began to flower in Britain in the wake of Melanie Klein’s discoveries in the 1930s. For about twenty-five years, his work has been well-known internationally in psychoanalytic, paediatric and psychiatric social work circles. In Britain, he has enjoyed a popular following for his radio talks, articles, and books on motherhood and child care. But his findings about the earliest phases of human development have not yet received the broader cultural consideration and application which they deserve.

For example, in his latter years, Winnicott turned away from clinical matters to concentrate upon the nature and location of cultural experience. This was the theme of his last book, Playing and Reality (1971). In my own researches into aesthetics, illusion, and the psychology of creativity, I have found the later Winnicott consistently clarifying and original. And yet I am always surprised at how few writers in this terrain cite Winnicott or realize the relevance of his work to theirs.

In part, this is the result of prejudice. Winnicott often denied he was an ‘intellectual.’ He insisted that ‘a writer on human nature needs to be constantly drawn towards simple English and away from the jargon of the psychologist.’ As his colleague, Masud Khan, once pointed out, Winnicott also manifested ‘a militant incapacity to accept dogma.’ He would not have needed to be reminded of The Poverty Theory. His radical materialism led him to stress that ‘mind is ... no more than a special case of the functioning of psyche-soma.’ None of this endears him to intellectuals. Paradoxically, his scepticism about intellectualism was one factor which helped him to become perhaps the best psychoanalytic theorist of infancy to have emerged anywhere since the last war.

‘The word infant implies “not talking” (infans),' he once wrote, ‘and it is not unuseful to think of infancy as the phase prior to word presentation and the use of word symbols.’ He stressed that the infant depended on maternal care based on ‘maternal empathy’ and not on words, and he found a way of doing and writing psychoanalysis which respected ‘the delicacy of what is preverbal, unverbalized, and unverbalizable except perhaps in poetry.’

Drawing on his reservoir of clinical experience, Winnicott demonstrated how innate ‘maturational processes’, can only develop satisfactorily through a ‘facilitating environment’ which, in the first instance, is the mother. Through the mother’s care, he maintained, ‘each infant is able to have a personal existence, and so begins to build up what might be called a continuity of being. On the basis of this continuity of being, the inherited potential gradually develops into an individual infant.’ But if maternal care was not ‘good enough’ then ‘the infant does not really come into existence, since there is no continuity of being; instead the personality becomes built on the basis of reactions to environmental impingement.’ It manifests a ‘false self.’

Winnicott was thus concerned with ‘the whole vast theme of the individual travelling from dependence towards independence,’ with the potential of becoming a fully human subject. By contrast, the currently fashionable Parisian psychoanalysis of Lacan and his acolytes conceives of only a ‘de-centred,’ disembodied ghost of a subject, constructed entirely through the impingements of the ‘signifying chain’ of a historically specific ideology.

This is roughly what Winnicott explains through the pathology of the ‘false self.’ I am sure that as the tenuous structures of such structuralism begin to look increasingly shaky, the relative strength and fullness of Winnicott’s contribution will become more and more apparent.

Winnicott, born in 1896, came from a wealthy, middle class background. His father was a Nonconformist sweet manufacturer who became Lord Mayor of Plymouth. After training as a doctor, he gravitated towards paediatrics: in 1923, he was appointed to the Paddington Green Children’s Hospital, where he remained for 40 years. That same year, however, he entered into a personal psychoanalysis with James Strachey, a prominent Freudian. This analysis lasted ten years.

Inevitably, Winnicott soon saw the significance of psychoanalysis for his work with children. ‘I am a paediatrician who has swung to psychiatry,’ he was to say later, ‘and a psychiatrist who has clung to paediatrics.’ His first book, Disorders of Childhood (1931), upset the paediatric establishment with its emphasis on the importance of emotional factors in infantile arthritis. ‘By being a paediatrician with a knack for getting mothers to tell me about the early history of their children’s disorders,’ he wrote, ‘I was soon in the position of being astounded by the insight psychoanalysis gave into the lives of children.’ But it was not a one-way process. Paediatrics made him increasingly aware of ‘a certain deficiency in psychoanalytic theory.’

At this time, Winnicott complained, ‘everything had the Oedipus complex at its core.’ Psychoanalysts traced the origins of their patients’ neuroses to the anxieties belonging to instinctual life at the four or five year period in the child’s relationship to the two parents. Winnicott, however, saw that infants and even babies could become acutely emotionally disturbed. ‘Paranoid hypersensitive children could even have started to be in that pattern in the first weeks or even days of life.’ Winnicott’s findings were disturbing to ‘orthodox’ analysts who ‘saw only castration anxiety and the Oedipus conflict.’

Although he was the only analyst in paediatrics in Britain, he was not the only one questioning Freudian orthodoxy by pushing back psychoanalytic insights into the earliest phases of life. Winnicott tells how Strachey ‘broke into’ their analysis to let him know about Melanie Klein who was then pioneering psychoanalytic work with children in Britain. Winnicott went to see her and began working in collaboration with her, but this was not easy for him. For all her brilliance, Klein tended to be a sectarian: Winnicott soon found he did not qualify ‘to be one of her group of chosen Kleinians.’ ‘This did not matter to me,’ he wrote, ‘because I have never been able to follow anyone else, not even Freud.’

Winnicott learned from Klein about technique, especially the use of play in the therapeutic process. He came to see the child’s manipulation of set toys and other forms of ‘circumscribed playing’ (for example, with a shiny spatula kept on the desk in his clinic) as ‘glimpses into the child’s inner world.’ Like Klein, he stressed that the child conceived of himself as having an inside that is part of the self, and an outside that is ‘not-me’ and repudiated—though this theory he later extended. Winnicott also valued Klein’s concepts of ‘introjection’ and ‘projection’: these she held to be mental mechanisms, of critical importance in early infancy, which developed in relation to the infant’s experience of bodily processes of eating and defecating respectively.

Klein emphasized the intense ambivalence—or opposition of love and hate—in the infant’s earliest relationship to the mother’s breast. She spoke of the defensive ‘splitting’ of the idea of the breast into ‘good’ and ‘bad,’ and attributed to the infant various psychic manoeuvres to keep these widely separated. All this led her to write of the ‘paranoid-schizoid’ position of earliest life, which, she maintained, was only superseded by the achievement and working through of a ‘depressive position’ in which the infant came to accept that the loved and hated breast was but part of one and the same feelingful person, out there in the world, separate from himself.

Winnicott, too, stressed the importance of the achievement of what he called ‘the capacity for concern.’ But he remained sceptical about Klein’s use of the model of madness to describe ordinary developmental processes. Although he reluctantly retained the term ‘depressive position,’ he rejected the ‘paranoid-schizoid’ model of early life. ‘Ordinary healthy children are not neurotic (though they can be) and ordinary babies are not mad,’ he wrote.

Indeed, the differences between these two thinkers are as important as their similarities. Klein, like Freud, rooted her psychology in a theory of instinct. She saw development as essentially determined by the operation of innate forces, the Life and Death instincts. Winnicott, rightly, rejected the concept of the Death instinct altogether. He stressed that a satisfactory state of being necessarily preceded a satisfactory use of instinct. This state of being he saw as being dependent on the relationship between the mother and the child. ‘Klein claimed to have paid full attention to the environmental factor,’ he wrote, ‘but it is my opinion that she was temperamentally incapable of this.’

Unlike many analysts who focused on the infant-mother relationship, however, Winnicott did not reject the idea of ‘primary narcissism,’ although he described it in very different terms from Freud. For Winnicott, in the beginning ‘the environment is holding the individual, and at the same time the individual knows of no environment and is at one with it.’ (This, of course, is the condition so often reproduced in mystical and ‘sublime’ aesthetic experiences.)

Freud had described the baby as an autoerotic isolate, forever seeking the experience of pleasure through the diminution of instinctual tension within a hypothetical ‘psychic apparatus.’ But Winnicott described the infant as being enveloped within and conditional upon the holding environment (or mother) of whose support he becomes gradually aware. ‘I would say that initially there is a condition which could be described at one and the same time as of absolute independence and absolute dependence,’ he writes.

Winnicott’s most brilliant theoretical work describes the way in which this primary state changes to one in which objective perception is possible for the individual. He rejected the idea that a ‘one-body relationship’ precedes the ‘two-body object relationship’; but this led him to ask what there was for the becoming individual before the first ‘two-body object relationship.’ He struggled for a long time with this problem and then, one day, he found himself bursting out at a meeting of the Psychoanalytic Society, ‘There is no such thing as a baby.’

‘I was alarmed to hear myself utter these words,’ he writes, ‘and tried to justify myself by pointing out that if you show me a baby you certainly show me also someone caring for the baby, or at least a pram with someone’s eyes and ears glued to it. One sees a “nursing couple”.’ Later, he put it this way: before object relations, ‘the unit is not the individual, the unit is an environment-individual set-up. By good-enough child care, technique, holding and general management the shell becomes gradually taken over and the kernel (which has looked all the time like a human baby to us) can begin to be an individual.’

Winnicott thought that the infant made his first simple contact with external reality through ‘moments of illusion’ which the mother provided: these moments helped him to begin to create an external world, and at the same time to acquire the concept of a limiting membrane and inside for himself. He defined illusion as ‘a bit of experience which the infant can take as either his hallucination or a thing belonging to external reality.’ For example, such a ‘moment of illusion’ might occur when the mother offered her breast at exactly the moment when the child wanted it. Then the infant’s hallucinating and the world’s presenting could be taken by him as identical, which, of course, they never in fact are.

In this way, Winnicott says, the infant acquires the illusion that there is an external reality that corresponds to his capacity to create. But, for this to happen, someone has to be bringing the world to the baby in an understandable form, and in a limited way, suitable to the baby’s needs. Winnicott saw this as the mother’s task, just as later she had to take the baby through the equally important process of ‘disillusion’—a product of weaning, and the gradual withdrawal of the identification with the baby which is part of the initial mothering.

Winnicott argued that it was only on such a foundation that the individual could subsequently develop objectivity or a ‘scientific attitude.’ He thought that all failure in objectivity, at whatever date, could be related to failure in this stage of development. Clearly, his conception of illusion had taken him beyond Klein’s sharp distinction between ‘inner’ and ‘outer’ worlds. This is what led him to his famous theory of ‘transitional objects and transitional phenomena.’ He began to describe what he called ‘the third part of the life of a human being, a part that we cannot ignore, an intermediate area of experiencing, to which inner reality and external life both contribute.’

Thus Winnicott drew attention to ‘the first possession’— those rags, blankets, cloths, teddy bears and other ‘transitional objects’ to which young children become attached. (‘In considering the place of these phenomena in the life of the child one must recognize the central position of Winnie the Pooh,’ he wrote.) He saw that the use of these objects belonged to an intermediate area between the subjective and that which is objectively perceived. The transitional object never comes under magical or ‘omnipotent’ control like an internal object or fantasy; but nor is it outside the infant’s control like the real mother (or world.)

It presents a paradox which cannot be resolved but must be accepted: the point of the object is not so much its symbolic value as its actuality. Winnicott often associated the infant’s relation to transitional objects with the insoluble disputes within Christianity about the ontological and/or symbolic status of the eucharist. The use of the transitional object, he said, symbolized the union of two now separate things, baby and mother, and it did so ‘at the point in time and space of the initiation of their state of separateness.’

In this way he came to posit what he called ‘a potential space’ between the baby and the mother, which was the arena of ‘creative play.’ Play, for Winnicott, was itself a ‘transitional phenomenon.’ Its precariousness belongs to the fact that it is ‘always on the theoretical line between the subjective and that which is objectively perceived.’ This ‘potential space’ he defined as ‘the hypothetical area that exists (but cannot exist) between the baby and the object (mother or part of mother) during the phase of the repudiation of the object as not-me, that is, at the end of being merged in with the object.’

Thus the ‘potential space’ arises at that moment when, after a state of being merged in with the mother, the baby arrives at the point of separating out the mother from the self, and the mother simultaneously lowers the degree of her adaptation to the baby’s needs. At this moment, Winnicott says, the infant seeks to avoid separation ‘by the filling in of the potential space with creative playing, with the use of symbols, and with all that eventually adds up to a cultural life.’

He pointed out that the task of reality acceptance is never completed: ‘no human being is free from the strain of relating inner and outer reality.’ The relief from this strain, he maintained, is provided by the continuance of an intermediate area which is not challenged: the potential space, originally between baby and mother, is ideally reproduced between child and family, and between individual and society or the world.

In every instance, however, it is dependence on experience which leads to trust. Winnicott saw the potential space as the location of cultural experience. ‘This intermediate area,’ he wrote ‘is in direct continuity with the play area of the small child who is “lost” in play.’ He felt it was retained ‘in the intense experiencing that belongs to the arts and to religion and to imaginative living, and to creative scientific work.’

I have ignored important themes in Winnicott’s work, such as the way in which he distinguished between psycho-neurosis and psychosis; his writing on the psychology of the psychopath; and his use of a technique of ‘psychoanalysis on demand’ which led some of his colleagues to complain that he induced ‘regression’ in his patients by adapting himself too readily to their needs. But I have done so because Winnicott’s description of the earliest infant-mother relationship, illusion, transitional phenomena and the potential space is undoubtedly his most significant contribution.

It would be foolish to pretend that Winnicott arrives at an adequate theory of culture. He does, however, begin to indicate a biology of the imagination, and of cultural activity, and to locate their roots in the period of the separating of the self out from that of the mother, which is peculiar to the human species.

His concept of the ‘potential space’ also begins to point towards a way of avoiding both ‘subjectivist’ accounts of cultural experience on the one hand, and ‘ideological’ explanations on the other. It is true that Winnicott considered that the ‘potential space’ can be looked upon ‘as sacred to the individual in that it is here that the individual experiences creative living.’ But he also saw that in many cultural activities, ‘the interplay between originality and the acceptance of tradition as the basis for inventiveness seems to be just one more example, and a very exciting one, of the interplay between separateness and union.’

Winnicott recognized that if the mother impinged too deeply into, or ‘challenged,’ the ambiguous character of the infant’s emergent potential space, then the latter’s potentiality for creative living would be seriously impaired. A similar occlusion of imaginative and creative potentialities may take place on a historic level when through, say, the proliferation of advertising, or of ‘socialist realist’ restrictions on artistic production the ‘potential space’ of the adult is diminished, or denied.

1980