MODERN ART chronicles a life-long rivalry between two mavericks of the London art world instigated by the rebellious art critic Peter Fuller, as he cuts his path from the swinging sixties through the collapse of modern art in Thatcher-era Britain, escalating to a crescendo that reveals the purpose of beauty and the preciousness of life. This Award Winning screenplay was adapted from Peter’s writings by his son.In September 2020 MODERN ART won Best Adapted Screenplay at Burbank International Film Festival - an incredible honor to have Shane Black one of the most successful screenwriters of all time, present me with this award:

As well as Best Screenplay Award at Bristol Independent Film Festival - 1st Place at Page Turner Screenplay Awards: Adaptation and selected to participate in ScreenCraft Drama, Script Summit, and Scriptation Showcase. These new wins add to our list of 25 competition placements so far this year, with the majority being Finalist or higher. See the full list here: MODERN ART

SEEING BERGER: LETTER TO FULLER

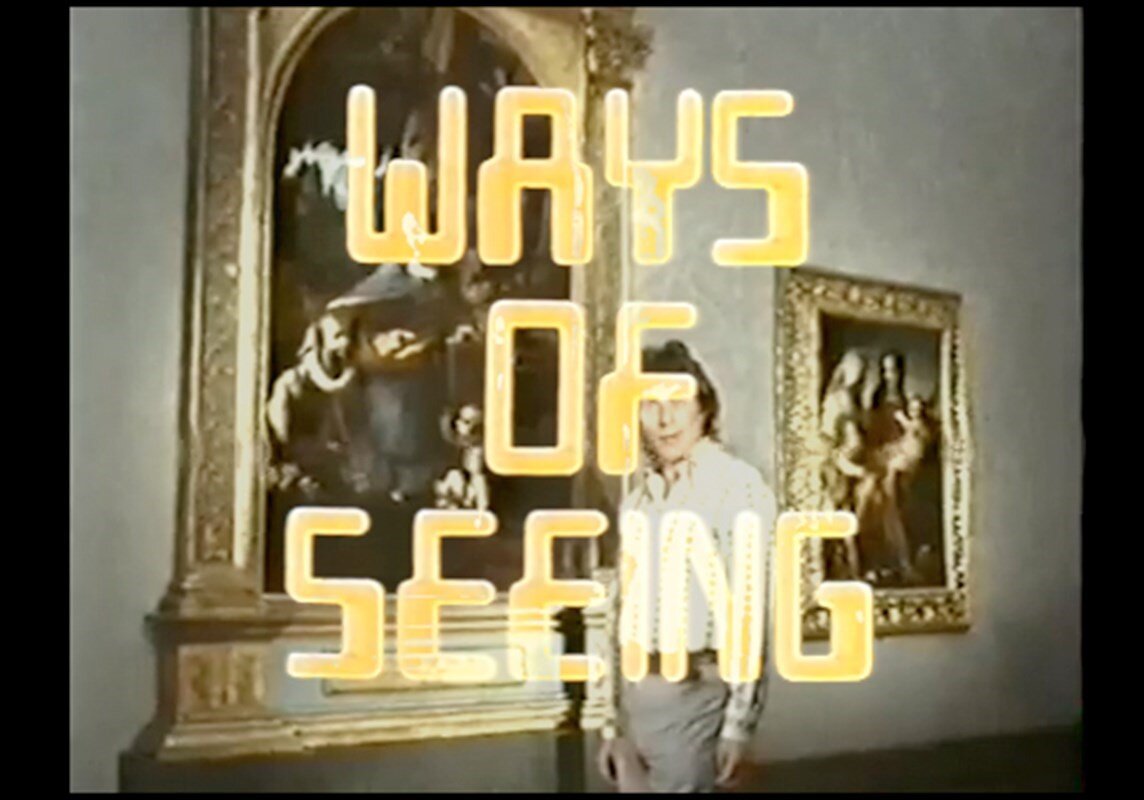

Mike Dibb, the director of John Berger’s film, ‘Ways of Seeing’ takes issue with Peter Fuller on his attack in NEW SOCIETY on Berger.

Mike Dibb directing Peter Fuller and David Hockney

Dear Peter,

Having been out of the country for several weeks, it was strange and sad to come back and read your assault (New Society, 29 January) on Ways of Seeing and John Berger’s bitterly ironic riposte. As the producer and director of Ways of Seeing among other films with Berger, as well as several films in collaboration with you, I want to tell you why I dissociate myself from your argument.

Clearly the bitter breakdown of your once close relationship with Berger has further distorted your reading of Ways of Seeing. If you feel that we were disingenuous in our references to Clark and Gainsborough’s Mr and Mrs Andrews, it is as nothing compared with the disingenuousness with which you treat the detailed text of both the television series and subsequent book.

To suggest, as you do, that Ways of Seeing, with its different and trenchant critiques of, among other things, the materialist obsessions of European culture, of the objectification of women, of the values of advertising, can now be seen as a Trojan horse of Thatcherism, is ludicrous. We never said that ‘advertising was the modern version of art.’

What we did try to suggest was that many of the pictorial codes of European painting now find a regular if more degraded place within advertising, with colour photography even more than oil painting providing a means for rendering the physical world ever more tactile and desirable.

We admitted that the essays touched only on certain aspects of each subject, that our principal aim was to start a process of questioning, that the survey of European oil painting was very brief and therefore very crude. We emphasised that there were important distinctions to be made between the experience of seeing the original painting and its reproduction, and between great works and the average ones, and so on and so on - all of which you slide over in your quest to get Berger as once you had used Berger to get Clark.

John Berger and Tilda Swinton

Reading your article made me go back to your first review of the series back in 1972, written for the radical weekly, Seven Days. It was also the first time we met. EJnder the heading ‘Berger’s anti-Clark lecture’ you celebrated the series at the expense of the ‘rubbish’ epitomised by Civilization, concluding with praise for the programme on women ‘which crashes through as many cultural myths in half an hour as Clark managed to fabricate and reinforce in the whole of his interminable series’.

Maybe today you want to vilify Berger as once you vilified Clark. But don’t you think it’s time you grew out of this need to have heroes and villains, to mix love and hate?

I noted R.B. Kitaj’s warning letter to you in Modern Painters: ‘I think the best art writing is about what the writer truly loves ... Personal hatreds will leave a stain, not the distinctive mark I hope you will leave ... be partisan of course, but there is no useful place for malevolence in art where there are precious few eternal truths.’ What I have always liked in the work we have done together is the fact that it has drawn only on your positive insights and analysis. We have never found space for abuse.

So in retrospect I rather regret that Ways of Seeing made any direct reference to Clark at all. There were only two references, but for those brief moments it personalised the argument leading to the possibility of the kind of crude oversimplifications of which I think you were guilty in 1972 and still are today (though in reverse).

Ways of Seeing was not conceived and mounted as a polemical riposte to Kenneth Clark. But because it appeared in the backwash of Civilization it was, I think, experienced and enjoyed as its antidote. As the director of the series, my main interest was in conceiving a form in which all the assumptions and conventions surrounding films about painting could be taken apart and re-examined. The first film was an attempt to give the dense text of Walter Benjamin’s Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, a playful and dramatic form. The theme of the last film on advertising emerged only during the making of the series.

The thinking behind the two essays on women and the European oil painting had existed in other forms well before Civilization was broadcast. Indeed your attack stimulated me to dig out the very first drafts of the scripts (in so many ways different from the finished films). Interestingly, there were no references to Clark whatsoever or to Mr and Mrs Andrews. I might even have been partly responsible for encouraging John to address this painting in the programme; certainly I will plead guilty (though I feel no guilt) to pinning the ‘Trespassers Keep Out’ sign on the tree behind them. (One viewer even wrote in that he had never noticed the sign before!)

And when you say that predictably Ways of Seeing has not given rise to any alternative art appreciation, I would point immediately to, among much else, important new work subsequently done on the representation of women, and on the analysis and decoding of advertisements.

Ways of Seeing, despite its sometimes overassertive simplifications, unlocked a whole spray of ideas to be argued over and refined by others. And frankly I cannot believe that art teachers and their students could seriously be undermined by it. It is not a sacrosanct book, just one to be used, together with much else.

And here I would like to tell you a little story. During my recent trip to Mexico I spent a short time in Tijuana, the fast growing border city just a few miles from the USA. It’s an amazing place, a surrealist and bizarre cornucopia where weekly waves of American tourists descend on and devour the kitsch end of Mexican popular culture. While I was there I went to an exciting exhibition. There was one young painter whose work I particularly liked. His subject matter was, among other things, the relationship between Mexico and the United States and he used every means at his disposal to express it: sensuous colours, collage, erotic shapes, an old gramophone, photographs, references to popular art, feathers transformed into fighter planes, and so on and on. It was full of wit and intelligence, political awareness and huge love of his medium - even when talking to me in a bar he doodled continuously.

John Berger

I asked him about influences and he replied immediately, Ways of Seeing. It was a moment to reflect on when that same series is being burdened with spawning the reactionary postures of Gilbert and George. But it becomes clear to me that by blaming Berger for Gilbert and George, you can conveniently, in one hurtful and surprising paradox, appear to kill two birds with one stone. But I’m afraid I’m not convinced. Writing in a spirit of revenge may feel sweet to you, but it sours your argument and saddens me.

You see, like you, I value the films on which we have collaborated, but, what may seem odd to you, find no contradictions between our most recent film Naturally Creative and Ways of Seeing. Each used a different means, for a different end, at a different historical moment.

And just for a moment consider the range of John Berger’s own writing about art. His essay, ‘The white bird’, could have been a text for Naturally Creative. And a few years after Ways of Seeing he wrote one of his best and most moving essays connecting the act of drawing with the death of his father. It inspired me to embark on what became the two hour film, Seeing through Drawing. In that film (minus Berger), I tried to demystify and open up the significance of drawing, but using techniques completely different from Ways of Seeing. The two projects were for me complementary, the one polemical, the other reflective and discursive.

In filming with you and in films with others, I always try to connect areas of thought often kept separate by the institutionalised divisions of academic discourse, taking art away from the specialised preserve of the art historian, and ideas out of the confines of the university seminar, seeing where they touch psychoanalysis, politics, history, science and people’s everyday experience of living and working.

The richness of the films is a product of the richness of the synthesis which film allows. This in turn depends on our ability to use images mechanically reproduced, detached from their original context. As we said in Ways of Seeing: ‘The art of the past no longer exists as it once did. Its authority is lost. In its place there is a language of images. What matters now is who uses that language for what purpose. This touches upon questions of copyright for reproduction, the ownership of art presses and publishers, the total policy of public art galleries and museums.’ Let me quote once more: ‘We are not saying original works of art are now useless. Original paintings are silent and still in a sense that information never is. Even a reproduction hung on a wall is not comparable in this respect for in the original the silence and stillness permeates the actual material, the pain, in which one follows the traces of the painter’s immediate gestures. This has the effect of closing the distance in time between the painting of the picture and one’s act of looking at it. In this special sense all paintings are contemporary. Hence the immediacy of their testimony. Their historical moment is literally there before our eyes.’

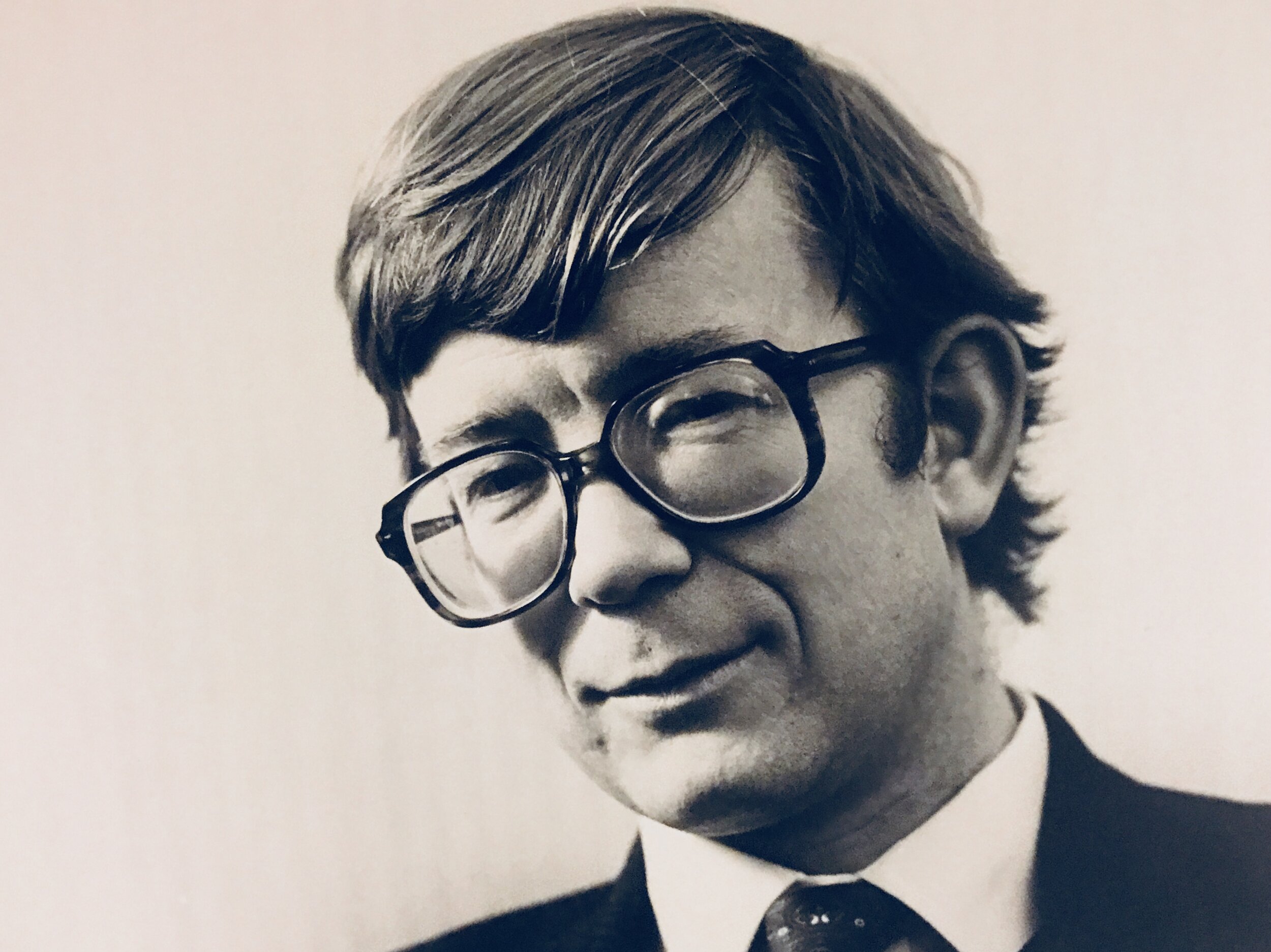

Peter Fuller

I don’t believe Ways of Seeing argues against looking at original works of art, any more than the vivid reproductions in Modern Painters pre-empt the need or desire of your readers to see the exhibitions on which many of the articles are based. But don't let’s have any illusions, either about the extent to which reproduction, and photography, in general, has changed our relationship to painting, or indeed about how the form, style and price of your new quarterly journal of the fine arts will mean it reaches one kind of audience and not another.

But enough is enough. Please heed Kitaj’s advice.

(New Society 22.4.88)